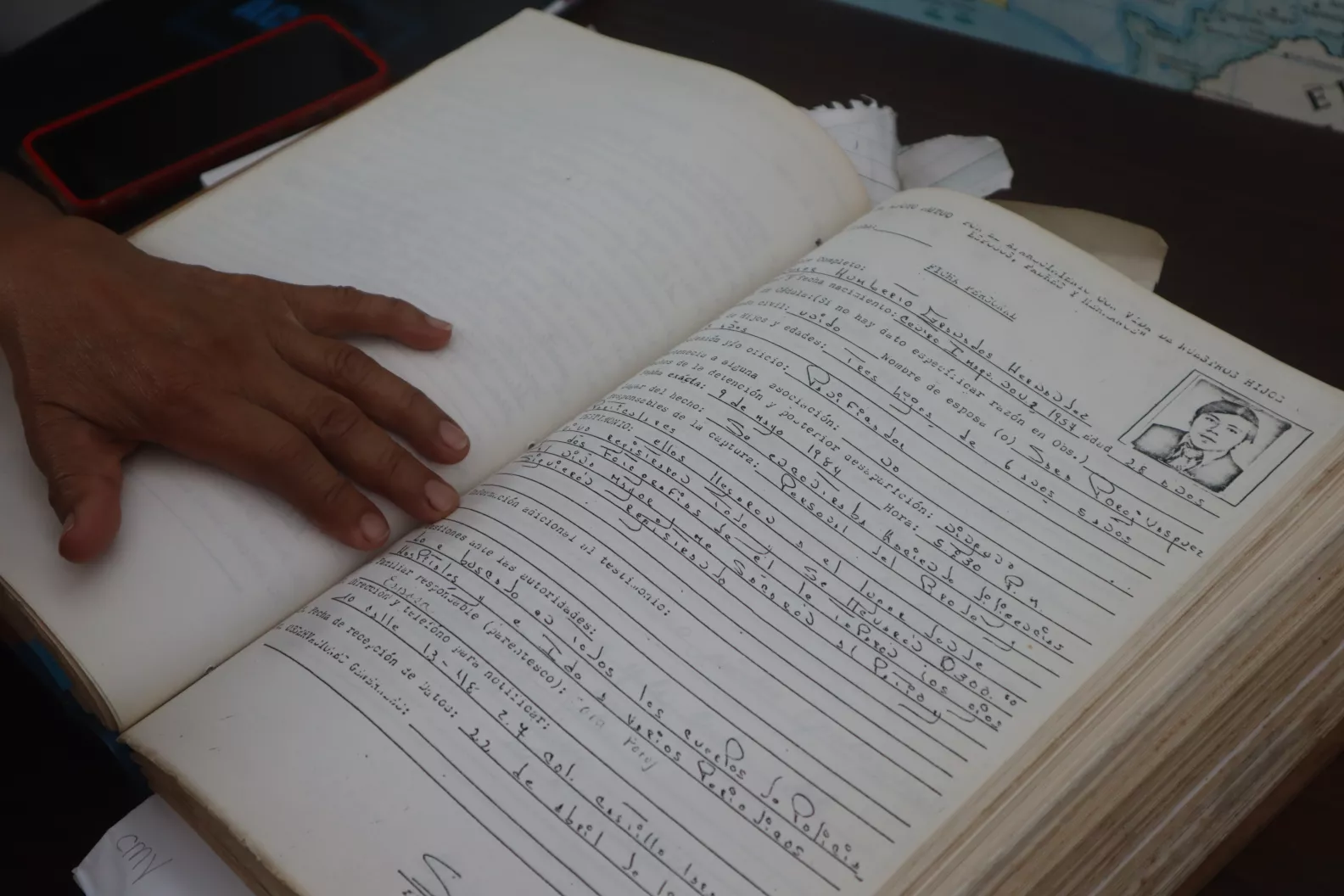

GAM’s archive was created with the organization’s founding in 1984. Through radio announcements, GAM’s founders told the public that they could report disappeared family members. Thus, they began creating an archive with all the cases that came their way. Carlos Juárez,1 the organization’s lawyer and head of the Archive for the past 15 years, highlights the magnitude of forced disappearances at that time, saying, “In just the first year, 200 families of disappeared persons joined the GAM,” despite the danger that doing so entailed. “They realized that it was a phenomenon that was happening everywhere, because people were coming from all over the country to share their stories and file complaints; it was a policy of war. And it was an indiscriminate practice, used against girls, boys, the elderly, women, and men. It became a weapon of war that tore many people from their homes, people who are still missing today, although their family members’ memories of them remain alive.”

Delving deeper into the unique nature of the GAM Archive, Carlos shared, “[The archive] comes directly from the victims; these are the firsthand accounts of people who suffered human rights violations. The archive is a vital tool for historical clarification, for example in trials, but also for other activities aimed at preserving memory and dignifying the lives of the disappeared. An archive like GAM’s is important because it preserves the living testimony of those who suffered the consequences of the armed conflict.”

The Archive is not closed to the public; rather, it can be visited by researchers, journalists, and family members. “The MP, through the investigations carried out by the Special Prosecutor for Human Rights, is our main user. Every week, they send us requests for information, and we respond to them as best we can.”

“Every year, people still come to share their stories or search for their loved ones. Second- and third-generation victims continue to search for their loved ones: their grandparents, aunts, uncles, mothers… This shows that talking about this issue, bringing the trauma of forced disappearance in Guatemala to light, is needed to heal this society. And we all need to understand that this can never happen to anyone ever again.”

Archival work in Guatemala was spurred by the discovery and eventual recovery of the National Police Historical Archive (AHPN) in 2005. The people who began this work helped create university degree programs in archival studies and promote recognition of the importance of archives in a variety of fields. This has been essential in the judicial sphere, for example, since evidence gathered from expert reports on AHPN documents has been included in many cases. Carlos recalls how people from the AHPN visited the GAM archives, saying, “They assessed the situation and told us that we had something valuable that we needed to start working to preserve. With their advice on how to get started, we took the first steps and began to seek support. We gradually found our way. We currently have at least 70 linear meters of information that’s been preserved to some degree. We’ve digitized 8.5 linear meters of information and have made significant progress in describing and classifying almost 45 meters.” The Archive continues to grow because, given the difficulties in obtaining justice in the country in recent years, “we have decided to preserve the Archive, because we also know that trials do not always progress as we would like. But an archive that preserves people’s living testimonies is a way to help bring closure to many families who are still grieving. I’m not saying that this is the answer, but we have heard people say: the fact that you have information, three or four pages about my father’s life, brings me great comfort and joy because it means that he has not been forgotten, that he continues to live and that there is still a place where it can be proven, on a few sheets of paper, that he existed and what happened to him.”

“An archive is a source of history and a guarantee of truth. And this Archive, more than anything else, is extremely human, as it contains highly sensitive information. That is why it is important that it be preserved, safeguarded, and widely known.”

The archive maintained by GAM has not been immune to attacks: twice, there have been thefts, which reduced its size. Carlos explains that “these types of archives face risks from the powerful forces that remain in Guatemala. Within the state, there are power structures that were responsible for and perpetrated human rights violations and that continue to wield a certain amount of influence in the justice system.”

“Right now, the MP is co-opted by groups that seek to erase history. In the past few years, the MP has obstructed and stalled transitional justice proceedings that seek to prosecute serious, widespread human rights violations. Now, all of the perpetrators [high-ranking military officials] who had been imprisoned are receiving special treatment. Not only are they being granted parole, but they are even being granted total freedom, and their cases are being dismissed.” That is why GAM considers it essential to have some kind of protection from international resources and national mechanisms to protect human rights and cultural heritage. “This is why GAM considers it essential to have some kind of protection from international instruments or national human rights and heritage mechanisms. Otherwise, we run the risk that our archives will be seized, altered, or destroyed, which has already happened. We have information here that, if it were disappeared, would erase any trace of these families’ existence. To pretend that these events never happened would be terrible for Guatemalan democracy and would do great harm to the future of the country, its youth, and the generations to come.”

1Interview with Carlos Juárez, Guatemala, 25 Apr 2025.