June 2021 marked the 10th anniversary of the unanimous endorsement by the United Nations Human Rights Council (HRC) of the Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. These Principles represent a step forward in the attempt to transition to a fairer economic growth model by recognizing the shared responsibilities of the State and the private sector in promoting sustainable development and protecting human rights.

However, the implementation of the Principles remains a challenge at the global level and, particularly, in countries rich in natural resources such as Guatemala. The expansion of the private sector and the intensification of competition for these goods have contributed to the strengthening of extractivist and exclusionary economic models. The implementation of these models has serious consequences for rural communities, indigenous peoples and human rights defenders who are very often the target of all kinds of attacks and threats when they dare to raise their voices against large-scale projects of various kinds: hydroelectric, mining, agribusiness, logging, etc. According to the Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders (Obs) and the Unit for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders in Guatemala (UDEFEGUA), it is possible to identify a sequence of aggression, threats, criminalization, stigmatization and even assassinations against those who defend land and territory.

“Today, the person who fights, who defends their environment, the rivers, the forests, Mother Earth and their community is persecuted and criminalized,” denounces María Caal Xol,1 leader of the Peaceful Resistance of Cahabón (Alta Verapaz), who has experienced human rights violations caused by the installation of hydroelectric projects on the Cahabón River. This pattern is repeated across various territories in Guatemala. Juan Lázaro, an ancestral indigenous authority of the Poqomam people from Santa Cruz Chinautla (department of Guatemala) highlights how: “We find it very difficult to denounce the abuses of the companies when they threaten us with potential reprisals. Then we start thinking about our family, about what would happen if something were to happen to us. Intimidation stops us, because we limit our actions and our denunciation of human rights abuses. They want us to keep quiet.”

According to María Caal, the criminalization of human rights defenders is one of the strategies most used to silence them: “human rights defenders are imprisoned as a tactic and are given unjust sentences.” Criminalization processes generally target community leaders and are part of a strategy to repress and silence the entire community. Lawyer Wendy López, director of the Indigenous Peoples Law Firm, gives as an example the case of criminalization of María Choc, a Mayan Q’eqchi defender against the damages caused by mining projects in Izabal. She was arbitrarily detained by the National Civil Police (PNC) after serving as a translator in a judicial hearing concerning the Q’eqchi’ community Rubel Pek “María is a Mayan woman, who speaks Q’eqchi, but who had the opportunity to study and therefore speaks Spanish. If you go to the community, nobody speaks Spanish. She is the element and the tool that the community uses to be able to express itself, and the persecution of the companies against her takes place because of this, so that the others are not heard.”

These criminalization cases are usually preceded by defamation and smear campaigns on social media. In many cases, the defamation and intimidation are loaded with strong racist, sexist and discriminatory connotations, with the aim of delegitimizing the communities’ struggles. “We suffer discrimination for being women, for being peasants, for being Mayan. They use different tactics to intimidate us in the different spaces we have as Mayan women,” comments María Caal. Felicia Muralles, member of the Peaceful Resistance of La Puya, which has been opposing a mining project between San José del Golfo and San Pedro Ayampuc (department of Guatemala) since 2012, explains how, “women, for example, are told that we join the Resistance to prostitute ourselves. Defamation has been a big obstacle for us, as well as criminalization. Many people end up withdrawing from the Resistance because of the defamation they receive and this has had many consequences for the organization, because before there were many more people participating but this has been gradually decreasing.”

The lack of guaranteed land rights experienced by indigenous communities makes them vulnerable to possible human rights violations caused by the implementation of transnational extractive projects. As lawyer Wendy López explains, “the company comes and says that it owns all the land and it has the titles. The community members, on the other hand, have absolutely no documents. Then the companies threaten them that they have to give up their land or they will be reported to the police. In exchange for the land they offer them a job, but generally with very bad conditions. This means that the whole family has to work. For the children this means that they will not have the opportunity to study. It is a form of modern slavery.” “Many of our compañeros in different territories in Guatemala who have been imprisoned, sometimes sentenced to more than 30 years, are falsely accused of trespassing, when we are the legitimate owners of our territories,” comments María Caal.

It is important to note that the abuses and attacks on defenders by corporate actors take place in a context where there is a clear imbalance of power between private companies and affected communities as “private companies exert considerable influence on States and ensure that regulations, policies and investment agreements serve to promote the profitability of their economic activities.”

”According to various reports, judges and prosecutors have contributed to the irregular application of criminal law by accepting false testimony, issuing injunctions without sufficient evidence, allowing unfounded prosecutions to succeed, and improperly interpreting the law to incriminate indigenous defenders.” “The person who defends Mother Earth is unjustly accused and condemned, without evidence. This happened in the case of my brother Bernardo, where it is evident how the companies have co-opted the justice system,” comments María Caal. Sharing her own experiences in legal cases, Wendy López points out that “in cases of criminalization, the Public Prosecutor’s Office (MP) should carry out the investigation impartially and using its own means, but in many cases the investigations are carried out in collaboration with personnel from the companies. The Public Prosecutor’s Office (MP) often does not even show up and it is the companies who provide the images, the videos, the descriptions, and they accept testimonial statements from people who were not even present when the supposed crimes were committed. This is serious, because everything is biased.”

Another problem is the lack of transparency, information and consultation with communities during the installation of projects in their territories. Number 18 of the Guiding Principles establishes that companies should identify and assess the negative human rights impacts of their activities through substantive consultation with potentially affected groups. In the case of indigenous peoples, they have the right to free, prior and informed consultation on any measure that may affect them, in accordance with Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization (ILO).

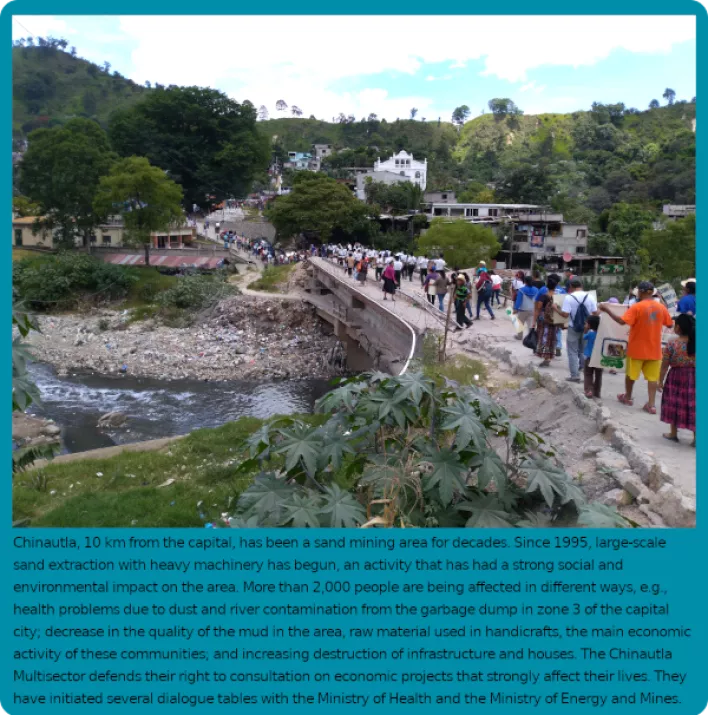

However, the right to consultation is constantly violated and information on project impacts does not reach the communities. In the case of the Peaceful Resistance la Puya, Felicia Muralles comments how “the information that first reached the communities was based on pure deception, because they told us that it was going to be a great development, that it was going to generate many jobs, that it was not going to cause damage, and many other lies in order to gain entry.” In Santa Cruz Chinautla, Juan Lázaro explains how “there has never been any consultation. There are mining licenses that were granted in 1988 or 1996, before the Ministry of the Environment even existed. There have been no environmental impact studies either. We asked for a study, but they don’t want to do one. The people are asking for consultation because there has already been so much abuse, with so much pollution the people are suffering from health problems.”

According to Wendy López, “there is a lot of corruption in the granting of these licenses. Another point is the falsity of the environmental instruments and the little interest the authorities have in analyzing what is happening or whether the data is accurate or not. They approve everything without any kind of study. There is a coalition between the State of Guatemala and the extractive companies, which means putting elements of the PNC or the Guatemalan Army at the service of the companies, among other measures.”

The installation of large-scale economic projects often causes significant environmental impacts, posing serious threats to health, access to water, food security and the right of communities to a healthy environment. Juan Lázaro notes how, for example, construction companies “come to dump garbage however they wish, using Santa Cruz Chinautla as a garbage dump. They come to dump whatever they want without any proper control. They dump waste and contaminated water in the rivers that supply the community. The environmental impact on our water sources is severe, because this water supplies almost 60% of the community. The issue of environmental impact is very complex and worries us a lot.” In the case of the Peaceful Resistance of La Puya, Felicia Muralles explains why they are opposing the mining project “in defense of water, because water in these communities is very scarce, so this is our main concern, because we are already in a part of the dry corridor and it rains very little”.

The Guiding Principles establish access to justice as one of their fundamental pillars. However, the difficulties faced by communities affected by corporate projects in accessing an effective remedy remain significant. “A first obstacle for accessing justice is the discrimination and racism present in the system. We are not seen as equals, so they attribute incidents to you, and because you are indigenous you are considered guilty of certain acts. The communities also suffer a lot from the lack of communication, in the sense that many are monolingual and unable to speak Spanish which does not allow them to have general knowledge of what is happening. Just as they are not understood, they do not understand the processes. Another important point is that many of the compañeros and compañeras in the communities are seeing that the leaders are being criminalized, and this criminalization has greatly affected community organization,” explains Wendy López.

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in even more obstacles to communities’ ability to report abuses. “The pandemic does not allow us to mobilize and denounce abuses because we cannot hold large gatherings. We can’t get together. But little by little we are starting to work again, trying to maintain the corresponding distance and the necessary measures,” says Juan Lázaro.

Widespread impunity for attacks on human rights defenders and for illegalities committed within the context of economic projects also demonstrates how communities face serious challenges in securing effective access to justice. “If we accept the justice systems are co-opted throughout the country then I believe in the end the denunciations do not favor us, but rather the companies, who use them to prove they are right,” comments Juan Lazaro. “Between the impunity and corruption, the extractive companies are saying to us that ‘you can’t fight us’. This leaves us in a situation of powerlessness,” says Wendy López.

In this sense, the genuine application of the Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights continues to be a relevant challenge and an urgent necessity for respecting the human rights of communities affected by economic projects. For María Caal Xol, the effective implementation of these Principles and human rights norms must begin with raising awareness among communities about their rights. “It is in the interest of the State and the companies that the brothers and sisters do not speak out and do not demand their rights. But today, day by day, girls, young people, women and men are realizing that these rights do exist. It is necessary to raise awareness in each community, teaching them their rights”. As Juan Lázaro points out, “we need to be respected as indigenous people, our territory needs to be respected. We have resisted for a long time in this territory and we will always continue to defend our lives, our rights, our land.”

1 The quotes from the various people that appear throughout this article were taken from interviews that PBI held with María Caal Xol, Juan Lázaro, Wendy López and Felicia Muralles.