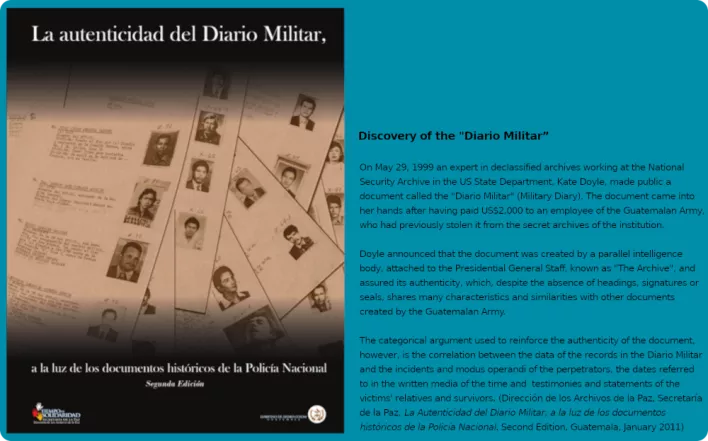

On May 27, 2021, eleven former military officers were arrested and charged by the Human Rights Prosecutor’s Office of the Public Prosecutor’s Office (MP) with serious human rights violations committed during the Internal Armed Conflict (IAC). These arrests are part of the “Diario Militar” (DM) case, referring to a document also known as the “Death Squad Dossier”, which contains detailed information about the capture and disappearance of 183 people between August 1983 and March 1985. It includes photos of the victims, a brief summary of their political activities and/or activism and, in some cases, the place of abduction and date of their execution. This is the first time in Latin American history that an official record, written by the perpetrators themselves, of kidnappings and executions of opponents of a military dictatorship, that of General Óscar Humberto Mejía Víctores (1983-1986), has been found.1 In June 2021, more than 35 years after these crimes were committed, the first phase of the statements from the officers accused of the crimes of forced disappearance, torture and murder began.

One of the victims in this case was Luís de Lión (José Luis de Lión Díaz), a poet, writer and educator from the community of San Juan del Obispo, in Antigua Guatemala. We spoke with his daughter, Mayarí de Lión,2 who told us about her father’s life and dreams, as well as her own dedication to honoring his memory and rescuing his legacy in the field of education. Mayarí is still searching for her father’s body, which remains unaccounted for.

Luis de Lión

Luis was the youngest of five siblings. He was born on August 19, 1939 in San Juan del Obispo, to a campesino family with Kaqchikel ancestry on his mother’s side. He loved nature and life, cared for children and had a great interest in the history of his country, Guatemala. He dedicated his life to the education and preparation of new generations and to the cultivation of the arts. For Luis, writing was a powerful weapon; reading and writing was a tool for understanding himself, shaping his own ideas and making decisions.

From a young age he worked as a teacher and literacy educator, doing internships in rural areas and with factory workers. He also established a library in his village and fought for the implementation of multilingual education. All his work was guided by a love of poetry and literature, which he saw as tools of empowerment for the impoverished classes.

As detailed in the DM, Luis de Lión was kidnapped on May 15, 1984, at the age of 45, on 2nd Avenue and 11th Street in Zone 1 of Guatemala City. He remained in the hands of his captors for 21 days before his murder on June 5 that year.

Mayarí de Lión’s struggle and the failure of the State to comply with the law

In May 1999, upon learning of the existence of the DM, Mayarí joined a complaint filed against the State of Guatemala before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) for its responsibility in the forced disappearance and extrajudicial execution of the people mentioned in the “Death Squad Dossier.” Through the mediation of the IACHR, the Presidential Commission for the Coordination of Executive Policy on Human Rights (COPREDEH) and Lión’s family reached a friendly settlement in March 2004. The government not only acknowledged its responsibility for the disappearance of Luis de Lión, but also made a commitment to comply with several reparation measures including: a State investigation into the disappearance, an awareness raising campaign about the importance of searching for victims of forced disappearance during the IAC, and public recognition of these incidents through the media.3 The State also committed to including Lión’s literary work in the national educational curriculum and to constructing a building in his native village to house the community library, a museum about the author’s life and a children’s playground. However, COPREDEH (closed in July 2020) has failed to fulfill these commitments.

How to Survive Enforced Disappearance: Reparation and Dignity for Victims and Survivors

The kidnapping of Luís de Lión tore his family apart. Mayarí says it was as if the foundation of their home had been removed. The military left no record in the DM regarding the whereabouts of the body, which has prevented them from closing the cycle of mourning. They are still waiting to find him. Mayarí said that this is very painful because it confirms that the same powers which caused the family and national tragedy continue to be present, operating under the same patterns of the past. This makes them feel vulnerable and is preventing her father from resting in peace. She laments that the commemorative plaque located on 2nd Avenue and 11th Street in Zone 1 of Guatemala City, the place where he was kidnapped, has been vandalized with hammers on different occasions: “it is as if they symbolically disappear him every time they do it.”

Mayarí’s life philosophy is characterized by the defense of non-violence, respect for all forms of life and the opposition to war. When a journalist once asked her what she would do to her father’s murderers if she ever had to face them, she answered: “for every day that Luis was tortured, I would give them an artistic, educational or cultural activity.” This way of understanding life is part of her father’s legacy. As a way of sharing this message of peace, and at the suggestion of a friend, she created the Luis de Lión Memory Days, which have been held every year for the lasr five years. Over the course of this celebration, the Luis de Lión Project invites people from different parts of the world to carry out artistic activities in memory of the poet. The purpose of this commemorative festival is the celebration of life and the vindication the missing persons’ dreams. The survivors and relatives of the missing are, therefore, not only perceived as victims, but as heirs of a great legacy. Otherwise there would only be room for pain, fear and uncertainty which can often lead to a state of depression. In Mayarí’s own words: “the Days of Memory invite us to recover our humanity. The challenge is to be fill the Museum with laughter, harmony and joy because in this way the cycle of forced disappearance is broken”.

Mayari’s security situation has been affected since the DM case has opened, but she continues to remain firm in her efforts and the children give her strength. She notes that, more than a judicial sentence, it is fundamental for the families of the victims to know the whereabouts of their disappeared, in order to honor them and close the cycle mourning.

Given that many years have already passed since the forced disappearances that occurred during the IAC, reparations, according to Mayari, should be given to the granddaughters and grandsons, in acknowledgement that the trauma experienced is passed on from generation to generation. Beyond a commemorative plaque, it is also necessary to identify the dreams of the disappeared person, recover and remember who they were and share their memory in public spaces, in the parks and streets of the city and throughout the country. Reparation, is not only about family but should also be social. “They are more than numbers, or names, they are people with qualities, stories, dreams and of course, also defects. The disappeared are human beings like us and therefore, they must be made visible as such. If these wounds are not healed, it will be impossible for Guatemala to build peace and achieve happiness.”

The Luis de Lión House Museum and his continued legacy

Luis de Lión’s artistic, educational, political and moral weight, led his daughter Mayarí to resume his work and struggles in 2004 so that they would not be lost. Without any help from the State, and using her own resources, she opened the Luis de Lión House Museum in the village of San Juan del Obispo, in Antigua Guatemala, in what was once the library founded by her father in 1962. The library functioned until the IAC broke out, forcing the books to be hidden to protect them from destruction. In 1992, four years before the signing of the Peace Accords, community leaders from San Juan del Obispo decided to reopen the library, naming it José Luis de Lión Díaz, in memory of the poet. One of the streets of his town was also named after him, to honor his memory and the educational work he did in favor of the population that who had experienced a situation of great vulnerability.

Over time Mayarí has been recognized for her efforts to make his father’s dream come true. Her social and educational work in the municipality has borne fruit, as she has managed to have a positive impact on the community without having to keep waiting for the State to fulfill its commitments. Nevertheless, not everything has been positive. Since Mayarí returned to San Juan del Obispo she has experienced various intimidations provoked by her work in defense of memory.

With respect to the House Museum, Mayarí recalls how from the beginning artists interested in the literary work of Luís de Lión began to arrive. Subsequently, they held music, painting, theater and poetry workshops for boys and girls. Currently, the main objective of this project is to turn children into ambassadors of peace and love for life, and for them to benefit from the activities of reading, poetry, music and any form of artistic expression, always imbued with gender equity and historical memory. Luis wanted all children in Guatemala to have access to education and artistic training, “he wanted every corner of the world to have a library.”

From a young age, Luis had promoted a literacy campaign in his village and created a study circle for his friends to develop a love of reading. In these spaces they discussed world literature, history and the contemporary situation. For Luis, education was not only about knowing how to read and write, but also about developing the ability to interpret and reflect on texts in order to orient oneself in the world and make free and conscious decisions. He was very clear about the power of words and the fear this inspires in non-democratic states. That is why this study circle was a cultural revolution in the municipality. As Mayarí points out, “today we can see the results of Luis de Lion’s work in his community. The educational processes take generations to manifest themselves, but his legacy is tangible in the quality of life and the educational level of local people.”

In the 17 years since the Luis de Lion Project began, an average of one thousand children per month have had access to the community library, between users and reading workshops in public schools, while hundreds of minors have passed through the Academy of Arts. The pandemic, however, has completely transformed the situation. Since the schools closed and for several months the Luis de Lión Project’s School of Arts was only able to offer marimba lessons at childrens’ homes.

Mayarí continues to strengthen her father’s legacy through the Luis de Lión Project, which has had a positive impact in the lives of the children who live in the foothills of the Agua Volcano through reading and the arts. It has been one way to fight against inequality, racism, impunity, violence and the structural problems of Guatemalan society. For Luís de Lión, children were “a blank piece of paper on which to begin writing a new history.”

Today the artistic and educational project consists of the San Juan del Obispo Community Arts Academy, the José Luis de Lión Díaz Library and the Luis de Lión House Museum, of which only the Museum remains temporarily closed, while the Library and the Academy continue to serve children despite the pandemic and the lack of economic resources.

1 Rímolo Molina, F. R., López Herrera, R., La verdad detrás del Diario Militar. Desapariciones forzadas en Guatemala 1982-1985. Guatemala, 2009.

2 Much of the information for this article was taken from an interview we held with Mayarí de León, on 13.09.2021 in San Juan del Obispo, Antigua Guatemala.

3 Francisco Roberto Rímolo Molina, Rubén López Herrera, La verdad detrás del Diario Militar Desapariciones forzadas en Guatemala 1982-1985, 2009