Communities of Resilient Populations (CPR): an example of mutual support for survival

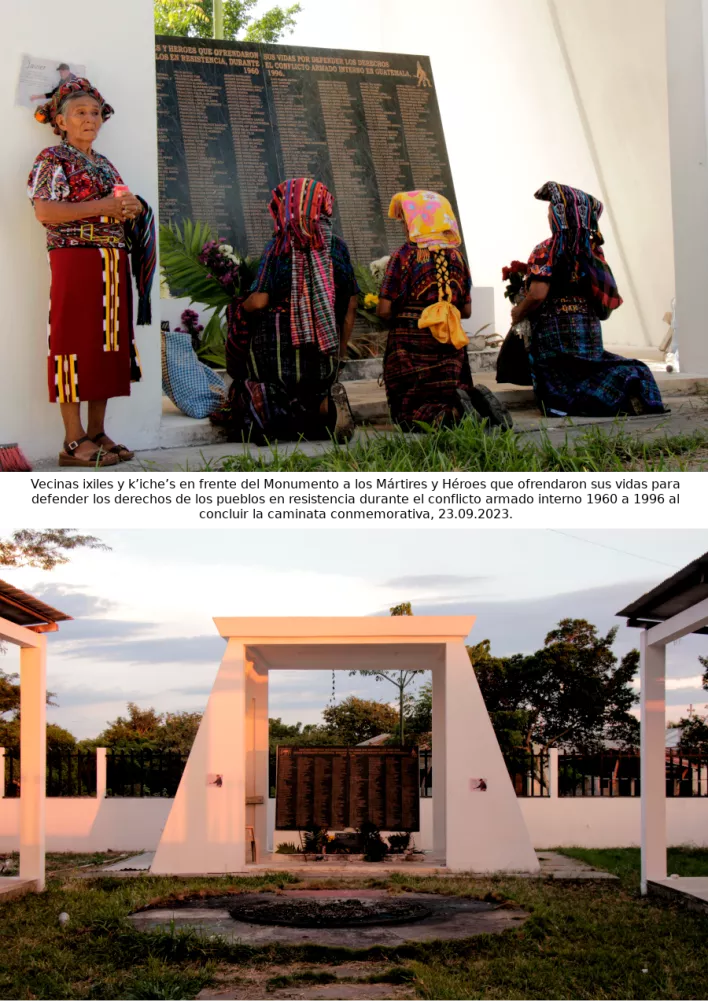

The collective book “El camino de las palabras de los pueblos” (The Path of the Peoples’ Words) draws on the memory of the indigenous peoples of northern Quiché. It explores how the Communities of Populations in Resistance (CPR) were a way people found to survive the state terror and its scorched earth policy that was carried out by the army throughout 1980s in the cruelest years of the “counter-insurgency war.”

Within this context of terror, the communities in this region1 had few alternatives. One was to surrender to the army and live in villages controlled by the military and providing compulsory service in the Civil Self-Defense Patrols (PAC). Another was to migrate to the capital, other regions of the country or abroad. There were also those who joined the guerrilla movements. But the alternative we discuss here relates to those who sought to resist and survive in the inaccessible hills and mountains, dodging army attacks.

This last option was taken by a multitude of families, and it was the strategy that allowed them to survive for 17 years. In the north of Quiché they found places that were difficult access but which provided shelter for many people and places to grow crops, keep animals and seeds. All this was possible thanks to an incredible level of organization, through which responsibilities were shared in various areas such as coordination, communication, production and trade, education, health and security.2

Living conditions in the CPRs were harsh. Food was scarce and every family experienced the death of a loved one for various reasons: hunger, disease, regular attacks by the army on people, crops, animals and other belongings. “The army destroyed our corn and they destroyed these very often. We spent six or eight months with nothing. We didn’t even have any herbs, we only ate banana root. Some died of hunger, others managed to go elsewhere to look for fish.” “Of my family, 18 died of hunger.”3

The support of other communities in the region also helped them to survive: “The solidarity of our brothers from Cabá, Sumal Grande, Salquil and other communities [was very important], they sent us food. These journeys of solidarity were long, with many days, 10 or 12, walking at night, evading fences, military patrols, civil patrols, but they finally managed to bring maize, seed and malanga.”4

As Rigoberta Menchú Tum points out, the CPRs were an example of community organization, “a challenge to the established order, to de facto violence, to state terrorism. And not only because they were survivors, but because they organized themselves to reject what their perpetrators represented: death, violence, humiliation, inhumanity. And they were persecuted for that, for having defeated death and for having told their story, a story that is also the story of the people of Guatemala, a story that speaks of the struggle for justice, for peace, for dignity and for better living conditions.” 5

“In reality, the army never came to our lands to fight the guerrillas, they came for our lands and in one way or another they stayed with our lands.” (J.T.T.)6

The state failed to fulfill its commitments

In June 1994, the Agreement for the Resettlement of Populations Uprooted by the Armed Conflict was signed. The purpose of this agreement was to recognize “the traumatic national dimension of uprooting during the armed confrontation in the country, in its human, cultural, material, psychological, economic, political and social components, which caused human rights violations and great suffering for the communities that were forced to abandon their homes and ways of life.” For this reason, the Government of the Republic undertook a commitment “to ensure the conditions that allow and guarantee the voluntary return of uprooted persons to their places of origin or to the place of their choice, in conditions of dignity and security.” In December 1996, the Agreement on a Firm and Lasting Peace was signed, which ended the conflict and allowed the previously negotiated agreements to enter into force.

“The proposal of the CPR-Sierra was to remain in the areas of resistance in the north of Chajul, to expand that territory for (re)settlement or (re)location, buying neighboring lands that were for sale, with the aim of forming a larger area in which the majority of the population that had carried out civil resistance in the area could settle. The objective was precisely to avoid dispersion, to remain in the region and not outside it, geographically dispersed, to consolidate the form of organization that had been in place during the armed conflict, which had proved to be successful, effective and efficient.”7

This proposal was rejected by the government. The state was looking for the exact opposite and did not accept the return of the population to their places of origin. Everything possible was done to divide the communities, so that they would live in different regions. In addition, internal fractures were created by offering them land that they had to manage through companies, insufficient land for the needs of the families and land parcels of different sizes. This caused internal conflicts in the beneficiary communities. Subsequently, the state granted land concessions for the development of mega-projects. This was the case of the Xacbal and Xacbal Delta hydroelectric plants on the Xacbal River, authorised in 2010 and 2012 respectively, without informing the population of the region.8

Faced with this situation, some 1,300 families from the CPR-Sierra took on the challenge of settling in places outside the areas of resistance, while they waited for the land that the state promised to provide them with. 350 families moved to Finca El Triunfo, located in Champerico, Retalhuleu. Virgilio García Carrillo, a member of the CPR-Sierra and one of the leaders of this community, explains that the land was not bought by the state. It was bought with funds from international churches that were obtained thanks to the international work carried out by the CPR delegations. “Unfortunately the government just shelved the Peace Accords and never followed up. For these new settlements the commitments were mainly land, decent housing, health, education, economic and technical funds for production, but this did not happen. The government did not take responsibility. They gave 100 small houses and there were 350 families, 100 small, unfinished houses, they were half built. The people had to look for ways to finish them. The Peace Accords were not fulfilled, land was given to us but it was bought purely with international support.”9

As Virgilio points out, not all the people from the CPR-Sierra went to El Triunfo; they dispersed to different departments and communities in the country: “The first farm that was bought was El Tesoro, in Uspantán, where 450 families settled. The second was the community of Maryland (in Retalhuleu), where 300 families settled. Then it was El Triunfo, where 350 families arrived. Other people returned to Nebaj to different communities; in total we were 23 CPR communities.10 Not all of us went to the same place.”

La llegada a la tierra prometida, otro reto para las CPR

“We left Chajul on September 24, 1998 and arrived here on the 25th. There were 350 families from Nebaj, Chajul, Cotzal, Chinique (Quiché), Chiantla (Huehuetenango) and Sololá”. But just then Hurricane Mitch hit the country from October 27 to November 4 of that year. Virgilio says that everything that had been achieved so far was destroyed, so some people got discouraged and 74 families returned to Quiché.

The situation that the 350 families found when they arrived was not what they expected, they had to live crowded together: “There were only two halls and 100 little huts prepared by a group that had gone ahead beforehand, with state funds, nothing more. Those who already had families of six to eight people were given one of the little houses. They were small houses with nylon sheeting around them and 6 or 8 metal sheets on the roof. We stayed in these small groups of houses for a year at the beginning. Then the land committee measured the land (11 caballerias) and distributed it. Each family built their own little house, with tin sheets on top and nylon around them. My parents, brothers and sisters were my neighbors. After 4 or 5 years, the European Community built us these houses in which we live now, for the whole community, 275 families, of three cement sheets and bamboo on top”.

Apart from the issue of housing, people had to look for ways to survive, generate income to buy seeds to grow. Most people went to work in neighboring villages, others to the sugar mill farms that were nearby, not as close as they are now though.

Those were hard years, as the land turned out to be very poor and the weather conditions did not help either: “there was a year when we sowed milpa (ancestral system of planting corn, beans and squash together), but we did not get a harvest because there was a drought and the milpa was lost.” Previously, this land was used to grow cotton, but just before the arrival of the families, it had been used as a cattle ranch. Because of this, the land was very worn out and badly burnt from the use of chemical products. They didn’t know any of this when they decided to move to this land. They thought that because it had been a farm there would be development, but that was not the case. They came from a cold land and arrived in a hot land without much rain: “for us it was a very sudden change; we didn’t expect it.”

According to Virgilio, in the early years “there was nothing to eat, there were no vegetables. We were used to eating vegetables that were produced in the fields, in the milpas, where there were all kinds of vegetables. There was corn, beans, güisquil, turnip, greens, all that. But here there were no vegetables, there was nothing, you had to go to Retalhuleu or Champerico to buy them. Now, every day, trucks and carts pass by selling products, because they see that there are people and they come to sell.” So the families began to plant corn for their own consumption and sesame to sell: “if some corn comes up, they also sell a little bit or exchange it for vegetables.” “Beans are very scarce, because here there is only one type of bean that grows, called ixtapacal. The cold earth bean, the bush bean or the pole bean, doesn’t grow here because this is very hot soil. The only thing that has been achieved here and that has been a blessing is soya, which is used to make cheese and milk. That did happen, but there was another hurricane when we sowed it and it destroyed everything. We raised it, we cut it, but it didn’t grow, the seed was lost. So “here there is only one annual harvest of milpa, because the winter is very short. Sesame is sown in August, between the furrows of the corn, when the corn is already bending.” However, there is a lot of fruit, “mango, coconut, jocote, cashew… we plant them for our own consumption. There is not much to sell because there is not enough land to grow it on, because if we plant in the good places, there is nowhere to plant the milpa, and if we have some cows for breeding, we also need pasture for them to eat.”

Eventually cattle became the main source of income in El Triunfo, but to keep them, land is needed: “At least we don’t work on the farms any more. The first few years we did, to ensure our survival, but then we didn’t. What my late father told me when we came here, is still fresh in my mind: before, we used to go down like pigs, like cattle, in trucks to the coasts, to the farms, but now we have a piece of land, it’s a shame that we go to work for the rich.”

Sugar mills, water scarcity and criminalization

Virgilio says that when they arrived 25 years ago, they were surrounded by cattle farms, there was no sugar cane. However, about 10 years ago, when the sugar mills were already operating, water began to run short: “Our wells dried up because the sugar cane farms use the water day and night to irrigate their plantations. The companies come to throw poisons, they come to fumigate with planes, they come to burn the cane, so everything is polluted, and the rivers are blocked and they take the water for their sugar cane fields, for their banana plantations, for their palm trees, it causes so much damage. The wells in the communities, in the fields, have dried up because the farmers dig deep wells. That’s why we started to fight against the sugar cane farms. “We have already learned that this is a dry strip of land that goes from here to the Mexican border, to Puerto Barrios, Izabal. However, there was always some rain here, but when the sugar cane companies came, they cut down all the trees and burned them. It used to be greener all around and despite the drought there was water.

In 2015, the communities affected by the sugarcane companies began to organize: “they invited us to a meeting where 18 communities attended. They elected one person from each community to form a council to address the problems of water, the use rivers, the drying up of lakes, the felling of trees, to protect mother earth. I was the auxiliary mayor at the time and it was my turn to go with COCODE to the meeting of the 18 communities. I became president of this Council of Communities, but the sugarcane companies sued four of us because of our involvement in the organization and that is why we experienced criminalization. For four or five years we couldn’t leave the department, we were under house arrest and we had to sign a register in Champerico on the 15th of every month. That was the problem we had, but thank God, we were happy when it was solved on 30 May 2023 and we were free. We did a good job, because now there are new communities where there used to be sugar cane. For example, the land of the Mam de Cajolá community, down here, used to be sugarcane, but the owner sold the land to the community.”

Another problem they face today is the lack of land, as El Triunfo has almost doubled in population and is now home to some 500 families. The land that was initially allocated to each family, 50 cuerdas, is not enough to distribute among the daughters and sons when they create their own families. The community established the agreement that land can only be sold among residents, as a form of protection for the community itself.

The lack of land, but also the lack of opportunities, increases migration to the U.S.. Migratory movements started about eight years after arriving in the community. Since then, entire families have left, leaving other family members to take care of their land and houses. Virgilio himself has two children who emigrated and he sees that this situation has no solution for the moment because “you can’t buy land, or build a good house, because there is no money, no income, because here we are barely surviving.” Despite this situation, most people who migrate do so with the idea of returning one day.

1According to the Historical Clarification Commission (CEH), the department of El Quiché suffered the highest percentage of recorded violations, 46%, followed by Huehuetenango with 16%. Between 1979 and 1983 they counted 250 massacres in the six municipalities of El Quiché: Cunen (6); Cotzal (31); Chajul (62); Nebaj (90); Scapulas (30) and Uspantán (31).

2Iniciativa para la Reconstrucción y Recuperación de la Memoria Histórica, El camino de las palabras de los pueblos. Magna Terra editores. Guatemala 2013, p. 250-251.

3Ibídem, p. 223.

4Ibídem, p. 224.

5Moller, J., Menchú Tum, R., Falla, R., Goldman, F. y Jonas, S., Nuestra cultura es nuestra resistencia. Represión, refugio y recuperación en Guatemala. Editorial Océano de México. México, 2004.

6Iniciativa para la Reconstrucción y Recuperación de la Memoria Histórica, Op.Cit, p. 253

7Iniciativa para la Reconstrucción y Recuperación de la Memoria Histórica, Op.Cit, p. 272.

8Ibídem, p. 280-285.

9Interview with Virgilio García Carrillo, June 14, 2023.

10They were originally distributed in 9 farms located in different departments: 4 in Nebaj and 1 in Uspantan, in Quiché; 2 in Retalhuleu; 1 in Suchitepéquez and 1 in Chimaltenango. But in 1998 Hurricane Mitch completely destroyed the Maryland farm in Retalhuleu and made it uninhabitable, so the families settled in other farms in the area or returned to the Ixil area.