in Defense of Mother Earth

“We are defenders of nature, of our sister earth, our sister water, our brother forest. It is a very broad and huge task, defending and being able to discover what our ancestors, our grandparents cared for: everything that was nature, which is life for all human beings… they taught us to respect, to live together with mother earth, with nature. That has been lost. We have lost a lot… the forests and the water, we have polluted the water sources, the rivers, streams and ditches.” 1

Ten years ago, in the municipality of Olopa (Chiquimula), a 25-year mining license for antimony was approved in the name of American Minerals S.A. This was done without prior consultation with the communities that would be affected by the mining project. Since 2016, the communities, which at the time formed part of the New Day Ch’orti’ Campesino Central Coordinator (CCCND), have demanded the closure of the project, as it represents a serious environmental problem with serious repercussions on the health of the people, as well as on the cosmovision of the Mayan people, for whom the care of nature is of utmost importance.

The arrival of mining

The Ancestral authorities from the Indigenous Council of Olopa and other community members assert that mining in this territory began approximately 35 years ago. Community journalist Norma Sancir, who has been reporting on the struggles of the Ch’orti’ people for years, explains that at that time the mining was mainly artisanal. Many people from the communities worked there without understanding the long-term environmental impacts, because at that time there was not much information or media, “but years later, after the mine was in the hands of the company, they brought in heavy machinery and leveled the hill. That’s when people became concerned.” 2

Ubaldino García, a community leader from Olopa, told us what his father witnessed: “when the mining started, people came and told us this was going to be a cooperative, so that the community would approve it. But, in reality it never belonged to the community, it was always private. At that time the ore was near the surface of the earth and as there was no road, they used to remove it on the backs of animals. Then they started digging tunnels. The oldest record of a license application dates from 1987, as the mining law in Guatemala dates back to 1985. The miners did not manage to obtain a license then, they continued to mine illegally though. The communities have always been in resistance.” 3

In 2007, the Observatory of Extractive Industries registered a license for exploitation which had been “requested by Guillermina Esperanza Guzmán Landaverry. The license originally sought the extraction of gold, silver, copper, platinum, lead, zinc and antimony. 4 months later, they requested a change for just antimony.”4 The license was approved in 2012, during the government of Otto Pérez Molina, without consultation with the affected population, as required by the International Labor Organization’s (ILO) Convention 169.

Despite the opposition expressed by the communities, the mining company began operations in 2016. This led to protests. Francisco Ramírez, a member of the Council of Indigenous Authorities of Olopa, told how the Resistance was founded when the communities of Olopa realized the negative impacts the mine was having on the water and the environment. This private initiative promoted by the state was not the kind of development they had been promised. It had to be stopped before the damage became irreversible.

“We wanted the company to respect our rights, because, as indigenous communities, we were not consulted. For some it meant development, but not for us. More than anything else, it meant the deterioration of our lives, our lands and our forests. And that is why we had to take action.”

Because of their work in defense of their rights, the community leaders began to receive death threats and experience intimidation, shots fired in the air and on the ground, and surveillance. In 2016 a prosecution process began against 21 people from the communities, but ended relatively quickly. The criminal prosecution ceased after two months when the judgement was deferred on condition that they would not approach the mine for a year. 5

Another strategy of resistance to the extractive projects has been to seek legal recognition as indigenous communities before the state of Guatemala, thus turning the community into a subject of law with specific guarantees. Following marches, sit-ins and arduous legal and bureaucratic procedures, during which they had to face racist attitudes and discriminatory treatment by the authorities, six Ch’orti’ communities achieved municipal recognition in 2018. With legal accompaniment provided by the Nim Ajpu Association of Mayan Lawyers and Notaries, 14 of the 22 indigenous communities in the municipality of Olopa had been recognized by the beginning of 2020.

Suspension of the mining license

In November 2018, the Resistance pushed for an “in situ” inspection of the villages surrounding the mine by the Ministry of Energy and Mines (MEM) and the Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources (MARN), who would complete the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA). Three months later, MARN presented its EIA certifying that the mine did not comply with neither environmental nor legal requirements and requested the official suspension of the license and the immediate and definitive closure of the mine. Despite the constant aggressions, the Resistance declared itself in permanent assembly and installed two peaceful sit-ins at the two entrances to the mine, in order to ensure that MARN’s decisions were executed.

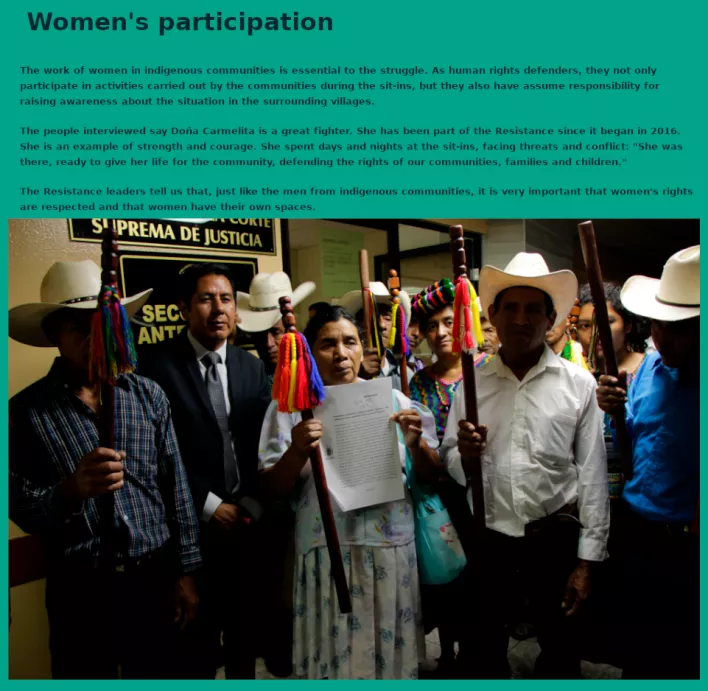

In August 2019, the indigenous communities filed an injunction before the Supreme Court of Justice (CSJ), demanding their right to consultation in the face of the company’s activities. At the end of 2019 the CSJ resolved this injunction by provisionally suspending the company’s mining license. This ruling became final in 2021 and the MEM was obliged to carry out a consultation with the population.3 However, the MEM filed an appeal and to this day the communities are still waiting for the judicial resolution.

Recovering ancestral land titles

The Olopa communities have been fighting for the defense of their extensive territory since colonial times. Their ancestors had to buy the land from the colonial administration at the price of two Tostones6 per caballería, acquiring a total of 635 caballerías. In the middle of the XIX century they managed to acquire the deeds and the title for the property in the name of the Común de Indios, also called Común de Naturales de Santiago Jocotán. The territory included the municipalities of Olopa and Camotán (Chiquimula), La Unión (Zacapa) and Copán (in the neighboring country, Honduras). But later, in the liberal period, this right was taken away and the land titles were transferred to the Municipality of Santiago de Jocotán.

Due to the above, the Indigenous Authorities of the Maya Ch’orti’ territory filed an injunction before the Constitutional Court (CC) in 2015 requesting the return of the co-ownership of the land. That injunction was granted and became final in July 2020. The municipality of Jocotán recognized the ownership of the land in the name of the Indigenous Communities but it ownership has not yet materialized for the Olopa communities.

In 2022, the indigenous communities of Olopa resumed their resistance activities, carrying out training processes to strengthen their organization and their struggle to restore and recover their ancestral right to the territory, to have their lands returned to them and to be recognized as subjects of rights. 7

PBI’s accompaniment

Due to the alarming increase in security incidents throughout 2021, including defamation and criminalization processes against them, the Council of Indigenous Authorities of Olopa, on behalf of their communities, requested PBI accompaniment to protect them in their struggle to defend their territory. This request was made as an organisation independent from the CCCND. PBI began to accompany them from this time onward.

In October 2022, PBI was present at a workshop with the media from Chiquimula. During the activity, the indigenous authorities called the media’s attention to the need to support them and be willing to accompany them in the different activities, as well as to disseminate information inside and outside of Guatemala. They also shared their concern regarding the racism and discrimination they constantly face when dealing with the state administration, which is reflected, for example, in the fact that they are not attended to or are denied public information when they request it. Their main concerns continue to be the lack of right of access to their lands and the environmental and health consequences caused by the installation of the mine.

Francisco Ramírez of the Council of Indigenous Authorities of Olopa, has called for the protection of our common home, Mother Earth: “We as defenders have been facing a monster that has been destroying our streams: the transnational companies are the ones that have been destroying our hills, our rivers, taking everything that is there, the greatest treasure that exists in our communities.”

1Interview with Francisco Ramírez, Ovidio Alonso and Blanca Hernández, Council of Indigenous Authorities of Olopa, October 15, 2022.

2Interview with Norma Sancir, October 2022.

3Interview with Ubaldino García, October 2022.

4Observatorio de Industrias Extractivas (OIE). Historial Proyecto Minero Cantera Los Manantiales, Guatemala, julio de 2021.

5https://dpej.rae.es/lema/criterio-de-oportunidad: “Facultad del Ministerio Público para prescindir total o parcialmente de la acción penal en contra de una o varias personas a las que se les atribuye la comisión de un delito”.