an Inspiration in the Struggle for Human Rights in Guatemala

“During the Mejía Víctores era, terrible things were happening both in the capital and in the countryside. Anyone who opposed the regime was detained, disappeared, or killed. Every day was truly hellish. In the morning, someone would be killed; in the afternoon, more people would be detained, disappeared, or kidnapped; and at night, we would bury more bodies. The situation in the capital became truly horrifying because it was a specific operation by General Mejía Víctores, a purge to wipe out what he considered to be the last remnants of the intellectual left: students, professors, and union leaders.” That is how Nineth Montenegro, one of the founders of the Mutual Support Group (GAM), recalls the political context in Guatemala in the 1980s.

Searching for their loved ones

“In that context, on February 18, 1984, my husband, Edgar Fernando García, was one of the thousands of people detained and disappeared. He was a student at the engineering department of the University of San Carlos and a worker at the CAVISA glass factory. Because of the tragic situation we found ourselves in, we took action [together with her mother-in-law, María Emilia García] and searched for him in different places, different prisons, different areas, requesting appointments and interviews. And that’s how we got to know other people who were in the same situation as us. In cemeteries, in prisons, in public spaces where bodies were found…that’s how we got to know other women, other families, and we thought that instead of acting individually, it would be better to act together to support one another and stand up for one another. And that’s what we did, and that’s how the Mutual Support Group (GAM) came into being on June 4, about three months after my husband’s disappearance.”

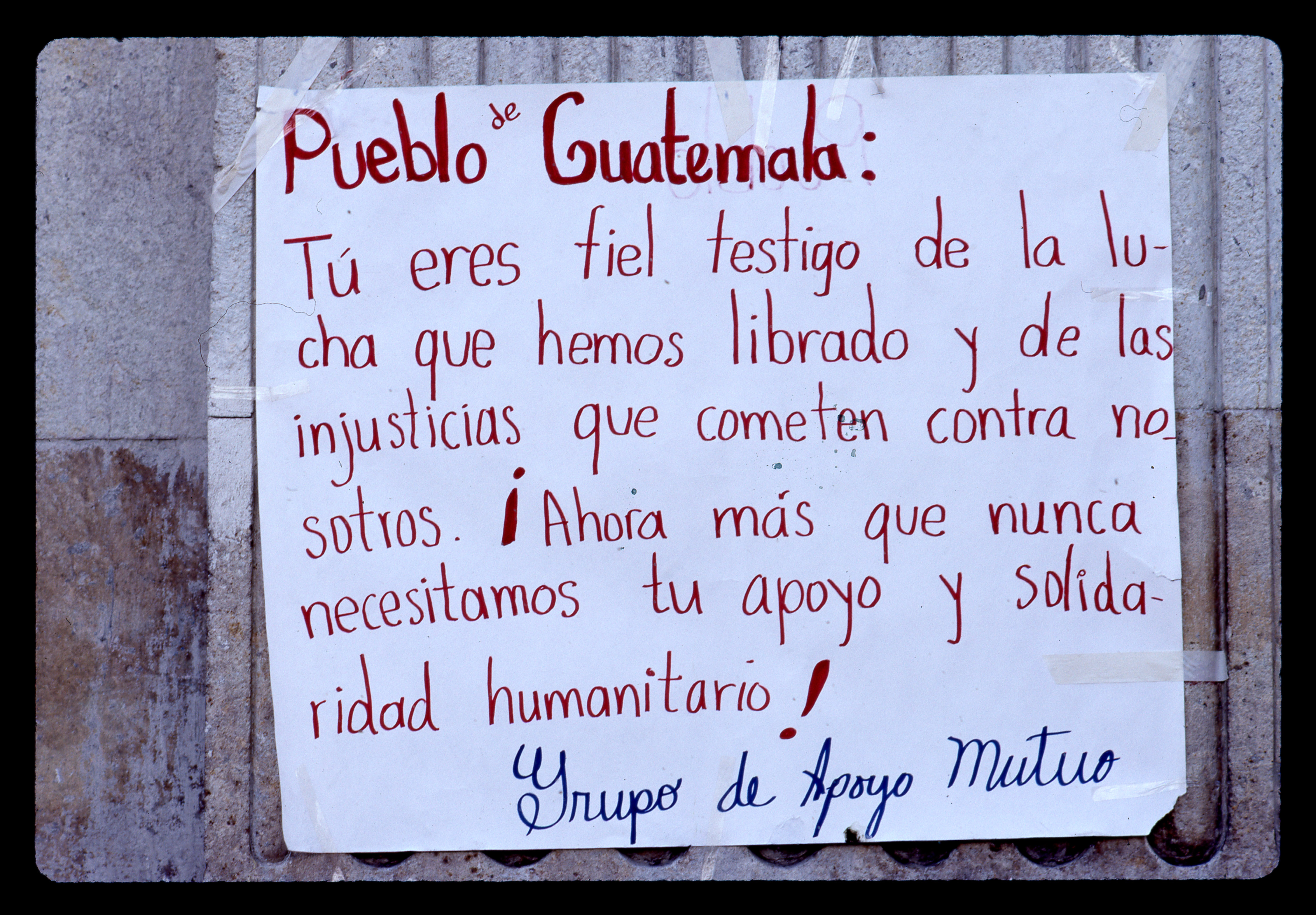

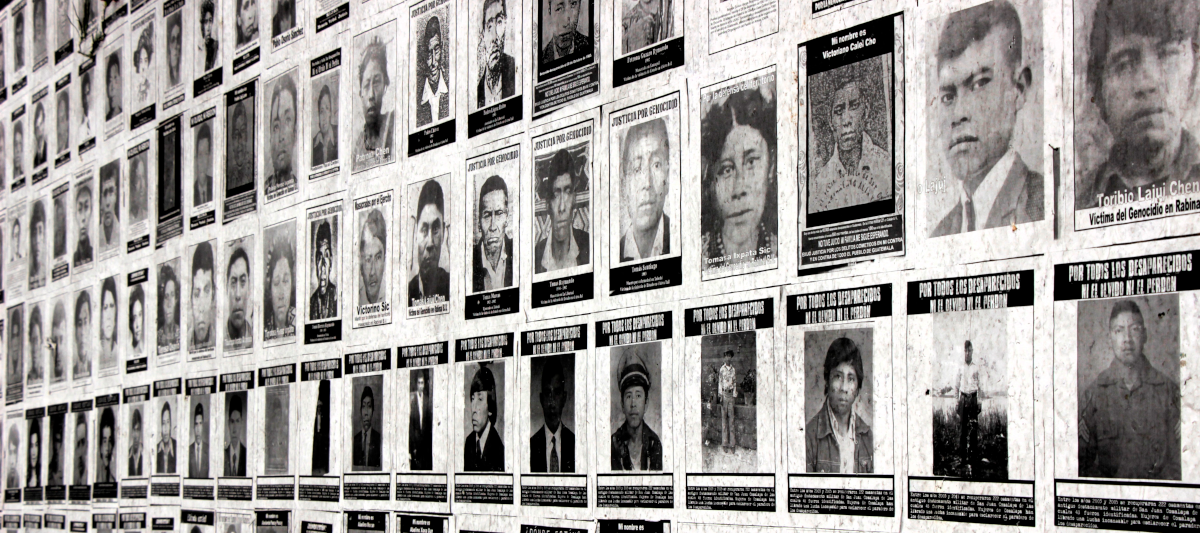

Thus, GAM became the first organization to publicly condemn the state for the arrests and disappearances that were being carried out, which totaled 45,000, according to the Commission for Historical Clarification (CEH), including 5,000 children.

Valentina Agustín and Jorge Hernández are the parents of Luz Leticia, who was disappeared on her 25th birthday on November 22, 1982. They have also been part of GAM from the beginning. Mirtala, one of Luz Leticia’s sisters, remembers how her father and mother searched for her in many institutions: they went to the morgue, the Roosevelt Hospital, the courts. During their search, they met other people who were also looking for their relatives. She shared, “That’s how they met. Despite my mother’s lack of education, she had to get involved in this struggle. She couldn’t stop, because she had to find Leti. And over time, my father learned all the stories of the other people who were searching: who they were looking for and the circumstances in which their loved ones disappeared. They looked for ways to contribute to this struggle. For example, my mother cooked food for the meetings.”1

Sara Poroj Vásquez was 24 years old and lived with her three children, aged 5, 4, and 3, in the Castillo Lara neighborhood of Zone 7. May 9, 1984 was the last day she saw her husband, Jorge Humberto Granados Hernández, 28 years old. “At around 9 p.m., they arrived at my house. I went to the door and saw them dragging my husband toward a white jeep and taking him away. There were bloodstains left on the street.” An hour before this incident, strangers arrived at their house, knocked on the door, searched the house, and took items, documents, and clothing belonging to her husband. They questioned her about his whereabouts.

“The next day they took me away, blindfolded me, put me in a car, made me climb down some steps, sat me on a cold metal slab. I was in my nightgown, and they asked me about my husband. I told them I didn’t live with him, that I lived alone. In the end, they didn’t do anything to me, and the next day they left me at my house. They told me not to report it so that nothing would happen to me.”2

Jorge Humberto was a baker and a member of a bakery workers’ union. He was organizing with them to demand better wages, “that’s why they disappeared him.” He was very active in the union, participated in protests, and was already aware of several disappearances. “He told me not to look for him if they took him away because I would never find him.” Sara did not listen to him and began a search that took her to hospitals and morgues. One day she heard an announcement on the radio inviting people who were looking for missing relatives to file a report at the GAM office. That is how she met them, without knowing that she would devote her life to this struggle. She became a member of the organization and continues to participate in its activities to this day.

PBI’s accompaniment

Shortly after it was founded, GAM requested a meeting with Peace Brigades International (PBI), an international organization that had been working in the country for a year. The meeting took place at PBI’s office. Nineth recalled her first encounter with the organization, saying, “I had heard about Peace Brigades—this is a very important topic for me—I think it was through the US embassy, because I went to the embassy and they told me about an organization called Peace Brigades. They gave me the address, and I went there. I took them a letter explaining my situation and asking for moral support in rescuing my husband. This was before the Mutual Support Group was formed.”

At that time, Peace Brigades had no clearly defined working methodology, as the organization was in the process of understanding the social struggles in the country so they could identify how exactly to support activists who were risking their lives to speak out against human rights violations committed by the government, which was militarized at the time. Thus began PBI’s response to the needs expressed by the Guatemalan people, who were suffering violence at the hands of the state during that bloody period in Guatemala’s history.

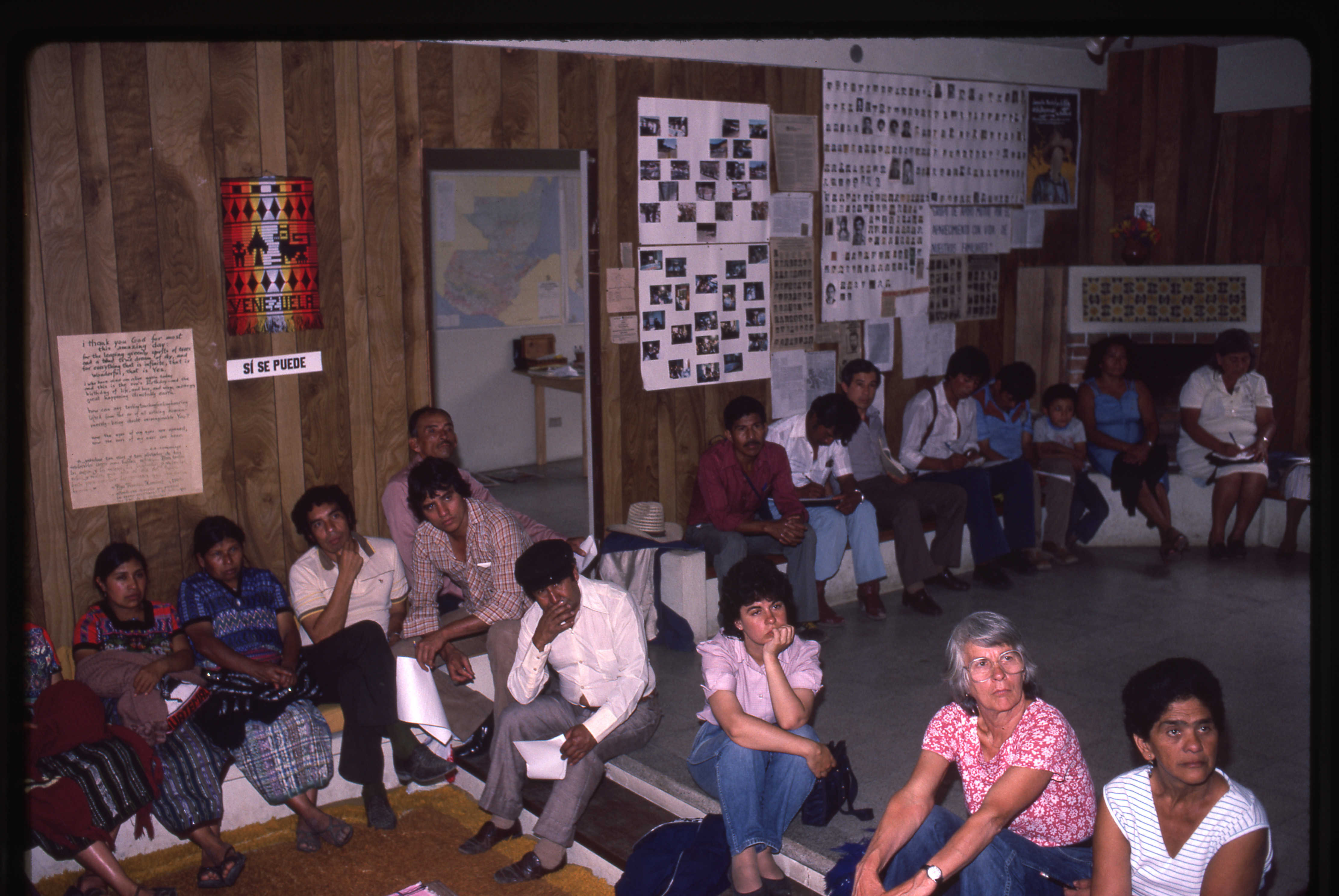

“When the Mutual Support Group was formed, we didn’t have a meeting place, so we would meet at Peace Brigades. For several years, GAM held its meetings at Peace Brigades, where we would talk to people about what actions to take to find the disappeared alive. The space served as our office, where we filed our complaints and our requests, planned our marches, and kept files on all the people who came to us. Because it was not just people from the capital who were coming, but also many people from the countryside, from rural areas, especially from Quiché, Chimaltenango, and Alta Verapaz, places that had been devastated by the violence and repression of those years. And so we began to take on cases, not just our own, but also those of all the people who had been victims of violence during the internal armed conflict.”

“Later, in addition to providing physical space, Peace Brigades contributed a lot by accompanying us at marches and demonstrations. They had a very mystical attitude, a strong commitment to pacifism inspired by Gandhi, and they put their own bodies on the line. When people wanted to beat us during a march, they would stand in front of us and form a shield… that was invaluable. They dared to attack us, but when they saw that there was a foreigner present, they stopped. The systematic accompaniment of all the marches, protests, walks, and vigils organized by the GAM provided invaluable support.”

“Unfortunately, just nine months after GAM was founded, between March and April 1985, GAM’s vice president, Rosario Godoy de Cuevas, and our secretary, Héctor Gómez Calito, were kidnapped. First, in March, Héctor was kidnapped as he left a meeting held at the Peace Brigades office in Zone 11, in the Mariscal neighborhood, on the corner, but we didn’t realize what had happened. They took him away in a car to an unknown location. We didn’t hear anything about Héctor until the next day, when he was found on the road to Amatitlán with his hands and feet tied behind his back and his tongue cut out, obviously dead. We were also accompanied by Peace Brigades’ members, who were with us at all times from the moment when we found Héctor’s body tossed on the ground, accompanying Héctor’s family, during what were horrible times for us because of what had happened. A few days later, just before Holy Week in April, Rosario Godoy, who was around 23 or 24 at the time, was kidnapped from her own car. Her one-year-old son and her 20-year-old brother were also in the car with her. We believe that they were going to a supermarket, but they never made it. They were found early in the morning, showing signs of torture. Even the little baby had had his fingernails pulled out. It was terrible, very painful, very shocking. Thus, GAM’s founding members also became victims of violence, simply for organizing ourselves and demanding that our relatives return alive and that those responsible for their disappearances be held accountable.

These cruel events had a profound impact on GAM members, some of whom were forced into exile. Others distanced themselves out of fear of suffering a similar fate, “while others among us pressed on.” During that difficult time, GAM received international support from the Latin American Federation of Families of the Detained and Disappeared, whose members “told me that I had to protect my life and that of my young daughter. That is when I asked Peace Brigades for help, because I knew that during Héctor’s wake and funeral, and later at Rosario’s, both my daughter and I were in terrible danger of losing our lives. Peace Brigades never once hesitated to support us. Immediately [after], I didn’t leave the Peace Brigades office. They organized a structure, a schedule, a calendar—I don’t know what—but from what I remember, starting on that day in April 1985 almost up until the signing of the Peace Accords, I was always accompanied by people from Peace Brigades, and not just me, but my little daughter too. In other words, from the time I left my house until I returned, there was always a member of Peace Brigades with me and another with my daughter. Peace Brigades always provided invaluable support, and I always say that if it hadn’t been for the support of Peace Brigades International, whose members protected us with their own bodies, even sleeping in our homes, we wouldn’t be having this conversation today. Life is very hard, but sometimes wonderful angels appear and somehow lend you a hand. For us, Peace Brigades was that wonderful angel who gave us moral support, support with their own bodies, risking their own lives. Peace Brigades became indispensable to our actions, activities, and our very survival.”

Challenging military and civilian governments

In the years following its creation, GAM became the most visible and coordinated organization. Despite constant threats and attacks, the women of GAM challenged the military governments first and, later, the civilian ones. In doing so, they paved the way for other organizations and future generations who continued in the struggle for human rights. In the 1980s, they carried out a series of high-profile public actions which, according to Nineth, “had an impact on society and sought to let the world know what was happening in Guatemala so that the state would be sanctioned.”

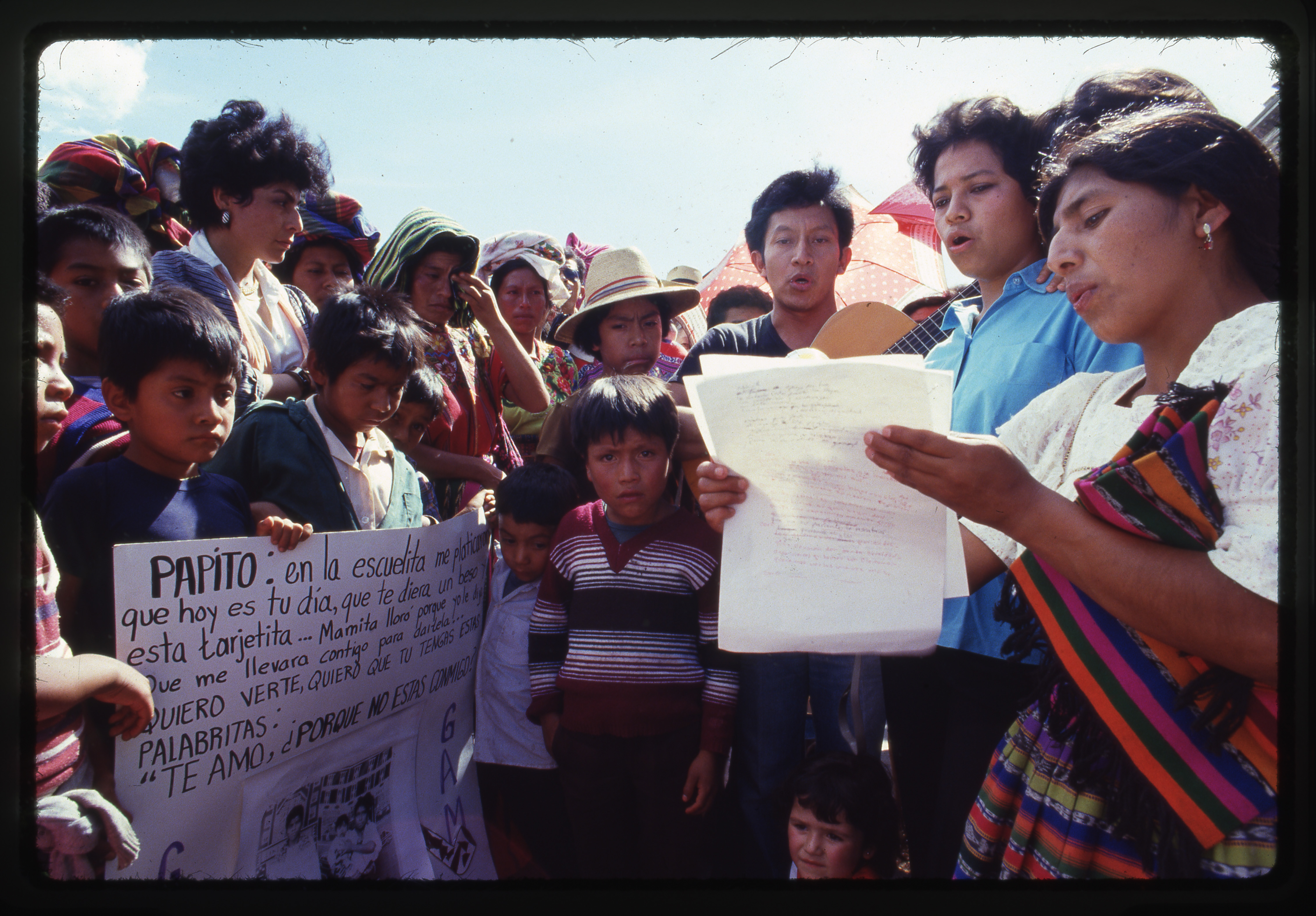

In October 1985, they took over the metropolitan cathedral to encourage the Catholic clergy to speak out against the disappearances and provide moral support, at the very least. On National Independence Day and Army Day, which featured military parades, GAM held a counterdemonstration to name the violence that the army committed against the Guatemalan people, both in the capital and in other departments. On Father’s Day, they organized a demonstration in which children held banners reading “Where is my dad?” They took over the National Palace and Congress to demand that the government return their loved ones alive and that members of Congress support talks with other authorities to establish a search commission.

They also rejected attempts to pass amnesty laws for human rights violations committed during the armed conflict.1 According to Sara Poroj, “We didn’t get a response from anyone. Not one administration took action to find out where our relatives were.” Nineth recalls that they had high hopes for the proposed transition process. Before he was elected, presidential candidate Vinicio Cerezo said he knew where the clandestine prisons were and that he would help them. But once he was elected, all he offered was “food for families as a form of compensation. It was hard because that wasn’t what we had asked for.” However, Nineth values the fact that “they actually admitted that they had our relatives, because they told us that they were guerrillas, communists, enemies of the state, and that they considered the GAM itself to be an enemy of the state.” Despite being under civilian rule, the use of forced disappearances against the population did not stop.

In the late 1980s, GAM began working to exhume clandestine graves. Sara was one of the coordinators of the exhumation team within the organization. She recalls that at first, “there was no support from the Public Prosecutor’s Office (MP), because they were afraid to investigate.” So, in “1988, we began the exhumations on our own, with the fire department.” But the process was soon formalized, and the MP and judges assumed their responsibilities. Sara highlights how complicated the procedures were, saying, “First, we collected testimonies from family members” in regions where clandestine cemeteries were known to exist, namely Chimaltenango, Quiché, Las Verapaces, and Petén. “We took the family members to the MP to give their statements. Then we had to obtain permission from the owners of the land where the Guatemalan Forensic Anthropology Foundation (FAFG) was going to dig” in order to identify the remains through DNA testing of the surviving relatives and the skeletons found in the graves. For 15 years, Sara accompanied the families in their search, which concluded with the burial of their loved ones, allowing families to give them a dignified farewell. However, Sara has never learned the whereabouts of her husband, who was detained and disappeared 41 years ago.

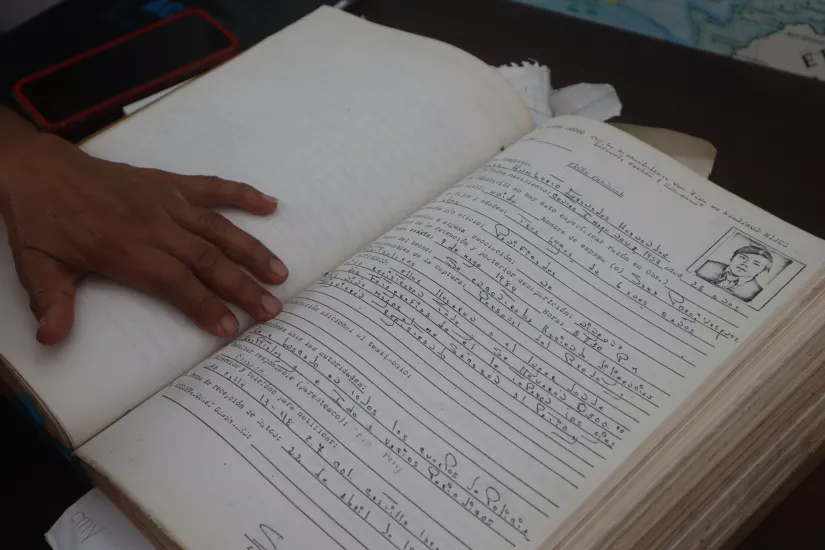

In the case of Nineth’s husband, she found crucial information in the National Police Historical Archive (AHPN). This archive was discovered in 2005 and contained a file on the kidnapping of Edgar Fernando, Nineth’s husband, which also identified the perpetrators. This evidence was crucial to clarifying the truth about police actions and the state agents responsible for these acts in one of the first trials for forced disappearances held in Guatemalan courts. All of this was possible thanks to official documents that the police themselves had kept at the AHPN. “In his [Nineth’s husband’s] case, justice was done, but much too late, and it was very painful because we never found him. His mother, Ms. Emilia, left this world without knowing what happened to her son. Although she was pleased that the Ministry of Education changed the name of the school where she had been principal. They named it after her son, Edgar Fernando García,” as ordered by the ruling of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights.

The family of Luz Leticia also managed to prove state institutions’ responsibility in the disappearance of their daughter and sister. After Marta Hernández Agustín, Luz Leticia’s sister, spent six months investigating at the AHPN, she managed to identify evidence that was handed over to the MP, leading to the indictment of Juan Francisco Cifuentes Cano, former head of the Fifth Corps of the National Police,3 as one of the perpetrators of this crime. Luz Leticia’s other sister, Mirtala, explains that “if my mom and dad hadn’t organized, we wouldn’t have gotten this far.” However, since she first testified in January 2023, the trial has been stuck at the admission of evidence stage.

What does the state owe them?

Forty years searching for their detained and disappeared loved ones, looking for their remains so they can heal the wound that, as Mirtala Hernández puts it, will remain open until they find out what happened and find their loved ones. Despite the importance of this issue, it is becoming increasingly difficult to obtain justice for these crimes against humanity, which tore apart countless families and the very fabric of Guatemalan society. The justice system has failed to respond to these essential demands for healing. Time is passing, and both the relatives of victims who have been searching for them for decades and the perpetrators themselves are dying. The perpetrators maintain a terrible pact of silence surrounding the crimes they committed against the population during the 36 years of the internal armed conflict (IAC).

However, Sara still hopes that one day the clandestine cemeteries will be opened. “May the memory of those of us who struggled to find our loved ones live on, may our work be valued for the sake of historical memory and justice, for we have done our small part along this long road.

Nineth, for her part, hopes that “all history books will tell the truth and that future generations will know and value what the rule of law and democracy have cost us in Guatemala.” To achieve this, she says, we need a state that “acknowledges what happened, honors the disappeared, and creates the conditions needed to search for them. Such disappearances must never occur again, and different opinions should be tolerated.”

“Forgiveness is for yourself – it helps you spiritually and makes you feel stable and healthy. But forgetting is impossible until you are able to see your family members’ remains.” Nineth Montenegro

Luz Leticia’s sisters, Marta and Mirtala, agree that the first thing they need is to know what happened to their sister, saying, “We want to establish the truth, get justice, and get our sister back.” Mirtala calls on “the current government to open the archives that confirm and prove who was responsible for all the crimes committed, because everyone’s life is important.” Marta adds that the state must acknowledge that it committed serious crimes against its citizens. It must reveal how all these military and civilian governments abused their power and showed a lack of humanity during the war, using brutality for their own benefit. It is important for the country’s historical memory that citizens understand this, so that something like this can never happen again.

GAM continues its work to this day. They seek justice for the various forced disappearances cases that have been reported to them since the organization was founded. The archive created from these cases serves as the basis for dozens of legal proceedings that their lawyers have brought forward. Notable cases include the forced disappearance of eight people in El Jute, Chiquimula, and the aforementioned case of Edgar Fernando García. Furthermore, together with other victim and survivor organizations, they have pushed forward the CREOMPAZ and Military Diary cases, both of which remain unresolved. Forty years after GAM was founded, and despite the organization’s significant achievements and enormous social work, much remains to be done to fully achieve its original mission. This requires that state institutions fulfill their obligation to deliver justice for the horrific crimes committed during the IAC.

1Interview with Valentina Agustín, Marta and Mirtala Hernández Agustín, Guatemala, 25 Mar 2025.

2Interview with Sara Poroj Vásquez, Guatemala, 29 Apr 2025.

3Also indicted for his involvement in the disappearances of people listed in the Military Diary.