March 22nd is World Water Day. This year, representatives from Guatemala’s diverse indigenous peoples and territories presented their findings and demands regarding the water situation to the government of Bernardo Arévalo. This was the result of 24 assemblies for water and life, held during the first quarter of the year in different regions. Over 600 people from more than 35 community organizations, including ancestral authorities, participated in these assemblies.

The water situation in Guatemala is worrisome. PBI has been a direct witness of this every time we have visited the different regions of the country where we accompany (see boxes). Water is not only scarce but also polluted, which leads to skin and gastrointestinal diseases. This pollution is often caused by waste and toxic agrochemicals from fertilizers used by agribusiness, which poison the soil and rivers. According to the Rafael Landívar University, “there is unequivocal evidence of widespread microbiological contamination (presence of fecal coliforms) in all water sources, regardless of the country’s territory, type of source (piped, river, spring, well) and type of area (urban or rural).”

Faced with the lack of response from successive governments, the indigenous and rural communities in various regions of the country, where this problem has become very serious, have made their own diagnosis which they presented to the Arévalo government and which we summarize below.

“Water and energy are not commodities”

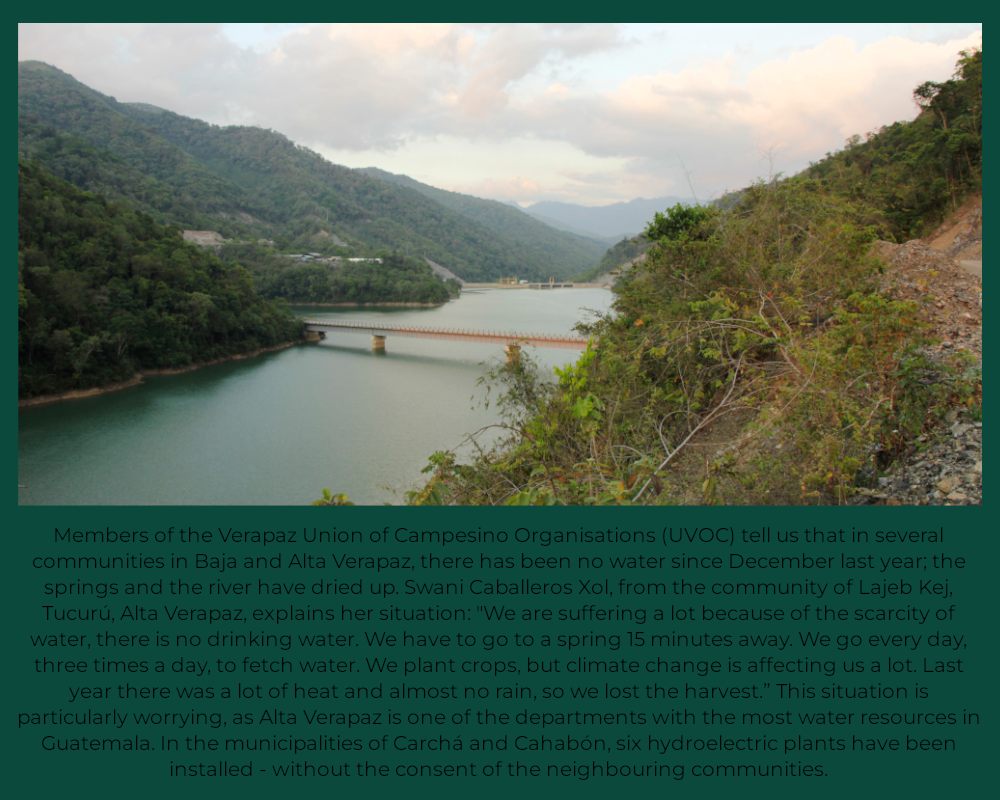

Francisco Rocael, of the Mayan People’s Council (CPO), criticized the General Electricity Law in his intervention, as it proposes an energy model aimed at satisfying the demands of industries, commercial centers and the regional electricity market. From his point of view, the right to electricity has become a business. Eighty percent of electricity generation is privatized and half of the electricity produced is being exported, resulting in the need to build new hydroelectric plants. Paradoxically, in the regions with the highest concentration of hydroelectric plants, such as Alta Verapaz and Quiché, the communities have no access to electricity. Rocael concludes that a new energy model is needed that recognizes the sovereignty and autonomy of indigenous peoples and strengthens local initiatives for the construction of communal hydroelectric plants, so that the communities produce and manage their own electricity. “We need a new territorial reordering based on hydrographic basins, based on conditions and demands of the communities and biodiversity.”

“We demand the right to consultation”

Diego Zamprano, from the Ixil area, shared concerns about the lack of recognition for community consultations. The State has shown no interest in recognizing the consultations carried out in more than 100 municipalities. It grants licenses for extractive projects that expropriate and divert rivers that are no longer accessible to the communities. He points out that this is also done without the companies complying with the requirement to carry out and present an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA). All this occurs despite the fact that the Constitutional Court has recognized the right to consultation in several rulings.

“Water is life”

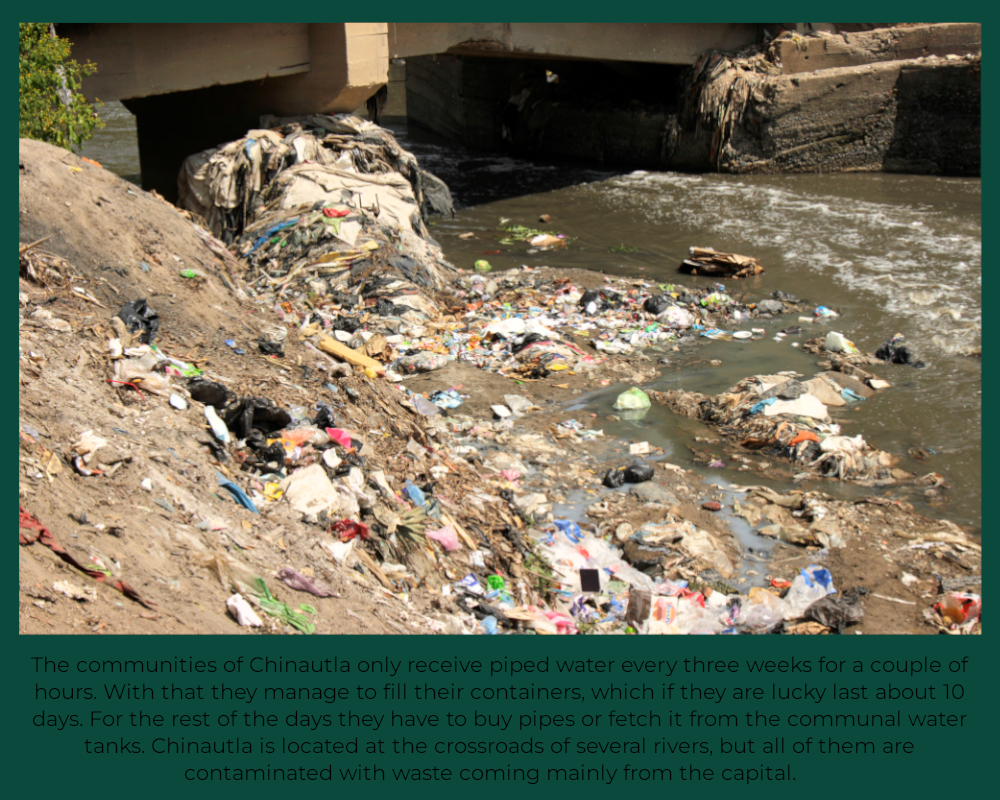

Judith Valle, representing Guatemala City and surrounding areas, recognized the privilege of urban communities compared to situations in rural communities and other departments of the country. Nevertheless, she highlighted how even in the capital the number of areas without water service is increasing, which has a direct impact on the health of the population. It also affects rest, since drinking water arrives at night and families cannot sleep because they have to be attentive to fill basins and tanks. The cost of the bills is also high. The alternative, water distributed in pipes, is polluted. The building boom in some areas of the city has added to this problem. This increases water scarcity for the metropolitan population.

“There will be peace if there is water”

Abelino Mejia, from the South Coast, warned about the diversion and retention of rivers that have left 49,000 people in the region without water, due to agribusiness activities (sugar, palm, banana, etc.). These activities have dried up the local wells, which has a serious impact on family crops. In each community there are between 35 and 40 children with malnutrition and entire families have to migrate to other countries to support themselves. In recent years 36 defenders have also been criminalized for defending the right to water. “Defending water is not a crime, defending water is defending life.”

Ecocide

The teacher Américo González, from the Qana’ch’och Water Defense Movement, which represents the lowlands of northern Guatemala (Sayaxché, Chisec, Fray Bartolomé de las Casas and Ixcán), denounces the land pollution from palm oil, rubber and sugarcane plantations. He shared a tragic experience of 2015 as an example of the damage generated by these companies. In the municipality of Sayaxché, the La Pasión river was polluted by the waste from a palm oil mill (REPSA) that affected hundreds of kilometers of the same river and its tributaries. This caused an ecocide of unknown dimensions. To this day there have been no legal proceedings against those responsible for this and other ecological disasters.

“What development has the Marlin Mine brought to San Miguel Ixtahuacán?”

Rosario Arteaga, of the Xinka People, requested a country free of mineral and non-mineral mining on behalf of the four Peoples of Guatemala. She pointed out that there are more than 300 mining licenses in the country and that they are presented as bringing development. Rosario asked: what kind of development do they really bring to the peoples; who benefits when the licenses are authorized; what does a mine leave to the State of Guatemala; what does the State do with the profit that is left? Indigenous Peoples have the right to consultation but this right is not being respected. The companies announce projects that supposedly benefit the people, such as reforestation, but in the EIAs the companies do not reveal how many trees they are going to cut down, nor do they talk about the pollution of rivers and water basins. Arteaga wonders who is solving the problems of pollution left by the mines in the towns; who is in charge of the lands that are left infertile by the pollution; what are the peoples who survive on agriculture doing? She also points out that when the people denounce and claim their rights, the State reacts with the militarization of the territories and the criminalization of the people who dare to raise their voices. Another important aspect she highlighted is that the lack of health care for the diseases generated by pollution makes the situation even more serious. There are studies that make it clear that the water is not fit for human consumption because it contains heavy metals and other pollutants, but the companies say that the water is fine. But then, Arteaga asks, why are fish and flowers dying?

Guatemala’s paradox: great natural wealth and great inequality

Bertilia Ramírez, delegate from the Ixcán Social Movement, stated that companies come to indigenous regions because this is where the country’s natural wealth is concentrated. “The State and national and transnational companies have come to our territories not to bring development, but to plunder our territories and to interpose their projects that threaten our existence as millenary Peoples. The projects are the greatest threat against our Peoples and the privatization of water is synonymous with death for indigenous peoples.”

“If there are no forests, there are no water sources and there is no life”

Vilma Angelica Chuy, from the Kaqchikel People of San Juan Comalapa, shared the effects of drought and the disappearance of bodies of water. She explained that indigenous peoples have an ancestral communication, respect and harmonic connection with water sources. Water is the blood of mother earth, it is sacred and is part of the cosmovision and cosmogony. Therefore, for indigenous peoples, water is not a resource but life and spirit.

Drought has reached their communities and has brought a massive loss of crops, which has decreased food production and the water available for human and animal consumption. In addition, 90% of all water sources contain microbiological pollution (feces) and its consumption without prior treatment is a health risk. Water sources that supply rural and urban areas are disappearing due to massive deforestation and inadequate solid waste management. This lack of water affects women the most, since their role in agriculture is crucial and they are responsible for feeding and caring for their families.

The Indigenous Peoples need the implementation of a sustainable irrigation system for farming communities. Subsidy policies need to go directly to the communities via their ancestral authorities, who are the ones who care for and conserve water and nature. Massive reforestation, environmental training in the communities for the care and conservation of water and the implementation of community reservoirs are also needed.

“Water is not a commodity”.

Maria Caal, of the Q’eqchi’ People, said that indigenous peoples suffer the consequences of the commodification of water. They are criminalized when they raise their voices to defend their rights and the rights of the natural elements. She has experienced this first hand, along with her family, due to the criminalization and imprisonment of her brother Bernardo Caal. Consequently, she demands that the government stop persecuting and criminalizing defenders who raise their voices against the destruction of nature. Because they are not the criminals. It is the companies that have stolen the rivers, water and nature. The Indigenous Peoples are the legitimate owners of the territories and natural elements. For all these reasons, she demands that the government carry out an EIA on the damages caused by the activities of companies in the territories. She demands consultations in each territory where companies operate and that the State no longer grant licenses to extractive companies. Without water there is no life: neither for people, nor for plants, nor for animals.

“Let’s defend water together, without water we cannot live”.

For Salvador Quiacaín Sac, Tz’utujil from San Pedro La Laguna, the generation of waste is not the problem, the problem is not knowing how to manage it. However, the increase in waste creates a risk for life. Sixty years ago, 70% of waste was organic, today 70% is inorganic and highly polluting. That is why it is urgent to control the management of solid waste.

People demand laws that count on their participation and that regulate the production of highly polluting waste. They demand that companies take social responsibility with respect to this issue. The fight against waste must be constant and count on the participation of all sectors. However, Quiacaín Sac points out that there are companies that benefit from the production of waste. The pollution of water and water sources by waste goes against human life.

“We demand recognition for water as a living being and the subject of rights”

Finally, Wellinton Osorio of the Chiviricuarta Collective presents the proposals and demands of the 24 community assemblies addressed to the country’s government:

- Massive reforestation days that are culturally appropriate and respect the diversity of native species that allow the restoration of life and diversity and ensure the filtration and growth of water sources in our territories.

- Community agreements and policies for the protection of water and for collective and community uses of water.

- Actions to recover water sources, rivers and community water sources.

- Recovery of practices and values that contribute to the care and defense of water, and which seek to involve new generations.

- Solid waste management in our territories.

- Food sovereignty based on access to water.

- Awareness campaigns on the importance of water and its care.

- A water law in accordance with the cosmovision and practice of our peoples.

- Environmental education to create awareness about water, forests, valleys and hills.

- Declare Guatemala to be free from open-pit mining.

- Cancellation of licenses.

- End the criminalization of people defending Mother Earth.

- Prohibition of the expansion of mono-cultures and the use of toxic agro-chemicals that irreparably damage water and soils.

- Prohibition of single-use plastic materials, and the promotion of the responsibility of the industries.

- State monitoring of the quantity, quality, availability and life of water.

- Serious EIAs should be carried out, and consideration should be given to not approving new housing construction projects in areas where there is no water.