International law recognizes and protects the rights of indigenous peoples, including the rights to freedom of expression and effective participation in decisions related to development projects or extractive activities that might impact them, whether directly or indirectly. One of the most widely recognized of these rights is the right to prior, free, and informed consultation, as enshrined in instruments such as Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization (ILO) and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. This right guarantees communities are heard and their decisions respected before any project is carried out in their territories. This framework also recognizes the legitimacy of peaceful protest as a form of active participation, especially when indigenous peoples’ collective rights are violated.1

In Guatemala, these international commitments were formally established with the ratification of ILO Convention 169 in 1996 and were subsequently reinforced by the jurisprudence of the Constitutional Court (CC), which granted constitutional status to the provisions of the Convention. This jurisprudence stipulates that “all mining reconnaissance, exploration, and exploitation licenses and hydroelectric licenses granted by the Ministry of Energy and Mines without consultation are illegal and arbitrary because they violate the constitutional right to consultation.”2 However, in practice, there remains a deep divide between the legal framework and the reality experienced by indigenous peoples. Back in 2013, the UN Special Rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples warned that the extractive model imposed on indigenous territories violates fundamental rights such as self-determination, rights to land and natural resources, cultural rights, and the right to a healthy environment.3 The Maya, Xinka, and Garifuna peoples are victims of, witnesses to, and reporters on the constant violations of international law in their territories.4

The signing of the Peace Accords in 1996 marked the formal end of the internal armed conflict and provided an impetus for Guatemala’s integration into the dynamics of the neoliberal economic model. This shift brought with it a development agenda focused on expanding extractive activities—hydroelectric projects, mining, monoculture farming, and oil exploitation—especially in indigenous territories. In this context, the State has not only failed to fulfill its obligation to protect the collective rights of indigenous peoples but has also endorsed and even promoted the implementation of these projects without prior consultation processes. Far from guaranteeing respect for indigenous rights, many institutions have acted as accomplices through dispossession, obstructing social protest, weakening community organization, and criminalizing territorial defense.5 In many cases, peaceful participation in territorial defense has come at a high personal and collective cost.

The Northern Transversal Strip—which spans the departments of Huehuetenango, Quiché, Alta Verapaz, and Izabal—has become an epicenter of socio-environmental conflict due to overlapping extractive interests—including oil, palm oil, nickel mining, and hydroelectric projects—on indigenous territories. Various forms of organization and resistance have emerged in response to this situation, led by ancestral authorities and community leaders acting on behalf of their peoples and in defense of their territory. These figures, whose legitimacy is recognized within the normative systems of indigenous peoples, are often ignored by state institutions and frequently targeted through campaigns of stigmatization, persecution, and criminalization.

One of the most emblematic cases of criminalization of territorial defense in Guatemala is that of Rigoberto Juárez and Ermitaño López, ancestral authorities and community leaders of the Maya Q’anjob’al people. Both led efforts to organize and resist the imposition of hydroelectric projects such as Canbalam I and San Luis, pushed forward by the Spanish company Hidralia Energía and its Guatemalan subsidiary Hidro Santa Cruz, without the consent of the affected communities.6 Because of their role in territorial defense, Rigoberto and Ermitaño were targeted by multiple criminal complaints, culminating in their arrest in 2015, along with five other community leaders, in what is known as the case of “the Huehuetenango Seven.”7

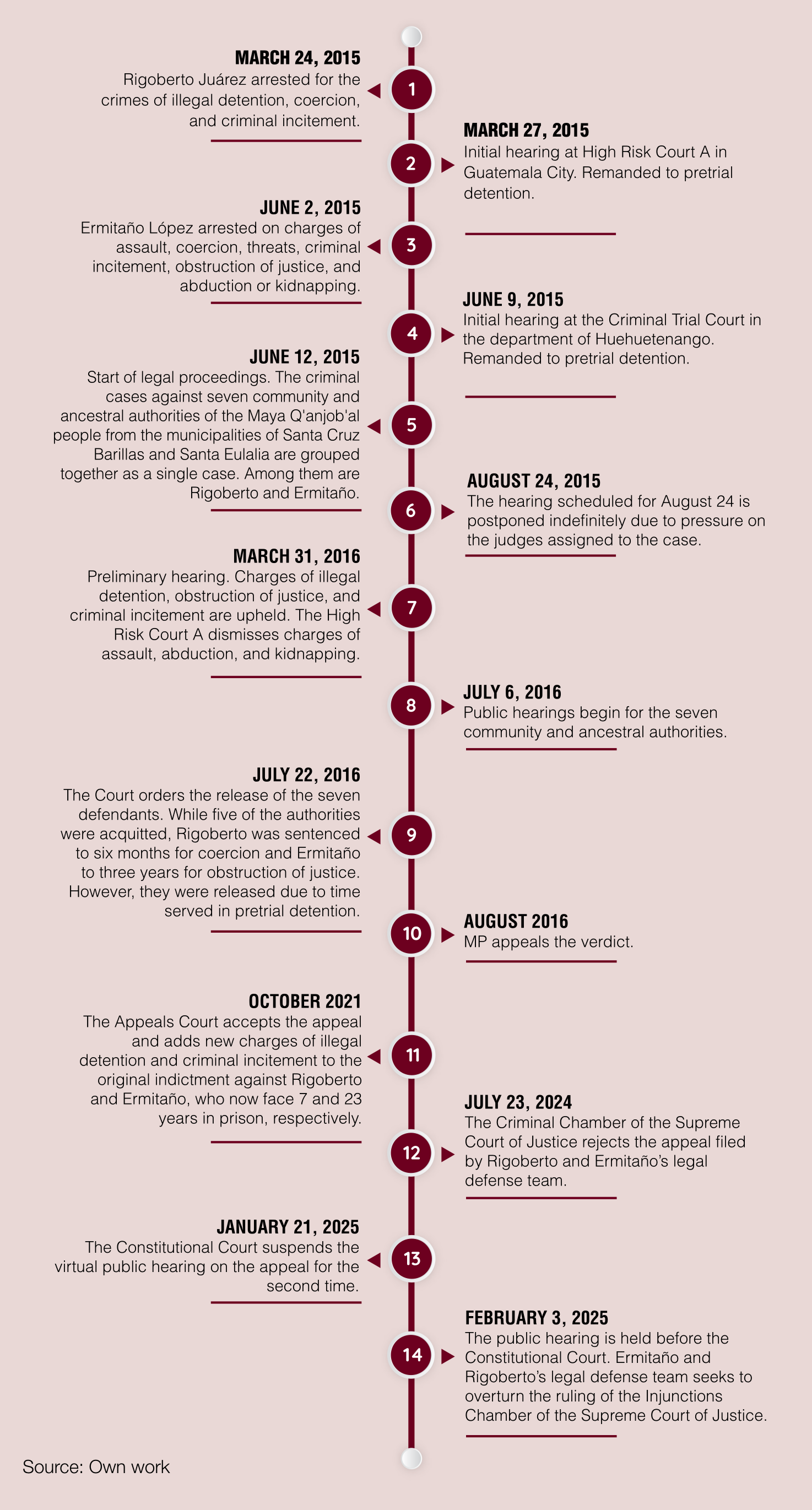

The following diagram shows the main developments in the case:

The leaders were criminalized for their participation in community demonstrations, protests, and conflict mediation efforts, especially in the municipality of Santa Eulalia. These actions, legitimately carried out within the context of territorial defense, were misrepresented by the Public Prosecutor’s Office (MP) as criminal acts in order to justify their imprisonment. Rigoberto was charged with detaining workers from the Hidro Santa Cruz company during a protest, coercion, and incitement to commit a crime, related to his role as an ancestral authority and spokesperson for the Resistance. Ermitaño was accused of illegal detention, coercion, threats, and incitement to commit crimes, among other charges. Both were imprisoned, not because they committed crimes, but because of their community leadership in defense of their territory, in the context of a systematic policy of criminalization against indigenous and community leaders opposed to the state’s extractive interests.

Both remained in preventive detention for more than 16 months. In 2016, High Risk Court A decided to acquit five of the defendants and handed down convictions for minor offenses (coercion and obstruction of justice) against Rigoberto and Ermitaño, who were immediately released because they had already served their sentences. In its ruling, the Court recognized that the community and ancestral authorities had acted legitimately by mediating to prevent violence, and that the evidence presented against them was insufficient to justify prolonged detention. The ruling showed that the arrests were politically motivated and that the judicial system had been used to criminalize community organizing and territorial resistance.8

Legal support from organizations like the Human Rights Law Firm (BDH) has been key to proving the legitimacy of Rigoberto and Ermitaño’s roles, under both national and international law. According to the BDH, aside from instruments like the Guatemalan Constitution—which recognizes indigenous peoples’ forms of organization—and ILO Convention 169, Supreme Court of Justice (CSJ) and CC rulings establish that ancestral authorities do not need to formally certify their existence in order for them to be recognized by the State. On this point, the BDH highlights the value of expert testimony in legal proceedings, which has helped show that indigenous authorities act on behalf of and in the interests of the community, not as individuals. In the case of Rigoberto and Ermitaño, expert reports prepared by Kiche’ sociologist Gladys Tzul Tzul and lawyer Ramón Cadena were decisive in proving the legitimacy of their actions as ancestral authorities and community leaders.

Gladys Tzul Tzul’s expert testimony showed that Maya ancestral authorities act as mediators under their own regulatory systems, recognized both by their communities and by the Guatemalan legal framework, under a collective mandate, and that their role in the conflict over the Hidro Santa Cruz project was to preserve social peace. She noted that their criminalization reflects a lack of knowledge of indigenous law and the state’s refusal to recognize its legitimacy.9 Likewise, lawyer Ramón Cadena showed that the State has used the judicial system to criminalize social protest, based on unfounded accusations and weak evidence, in order to politically neutralize ancestral community leaders like Rigoberto and Ermitaño, who were acting as legitimate authorities in accordance with indigenous law and the Guatemalan Constitution.10

However, in 2021, the Appeals Court ruled contrary to law, overturning the previous sentence and increasing the sentences imposed to 23 years of non-commutable imprisonment for Ermitaño and seven years for Rigoberto. This sentence was upheld by the CSJ in July 2024. The BDH argues that this decision violates the principle of reformatio in peius, which prohibits putting the defendant in a worse position than they would have been in if they had not filed an appeal. In addition, they point to serious procedural irregularities, such as the informal assessment of evidence by the Appeals Court—a power exclusive to the sentencing court—and the MP’s systematic practice of classifying non-criminals acts as crimes, relying on generic or ambiguous criminal charges, such as illegal detention, trespassing, threats, or incitement to commit a crime, to justify judicial persecution.11

For the BDH, the case is a prime example of the strategy of criminalization directed against human rights defenders in Guatemala, especially against ancestral authorities who legitimately represent their peoples. As they point out:

“This is a systematic policy of criminalizing authorities, leaders, and community members who defend their territory and resources. The Public Prosecutor’s Office employs recurring patterns, such as mass charges, failure to individualize conduct, and forcing facts to fit existing criminal categories, even when the conduct in question involves peaceful demonstrations or legitimate community defense activities.”12

From a legal standpoint, ancestral authorities are recognized both constitutionally and internationally. The Constitution of the Republic of Guatemala recognizes indigenous peoples’ systems of social organization, while ILO Convention 169, ratified by the State, establishes the obligation to respect indigenous structures of representation and community governance. Furthermore, national case law has confirmed that there is no need to formally certify authorities’ existence in order for them to be recognized by the State. However, in practice, the judicial system often requires documentary evidence to validate authorities’ representativeness, implying an implicit denial of the legitimacy stemming from community consensus. The BDH emphasizes that the staff carried by the authorities is a clear symbol of that legitimacy, conferred by community assemblies.13

The case is currently awaiting a ruling by the CC, which must hear an appeal filed by the defense. The appeal asks for the CSJ to reopen the case due to multiple procedural violations committed by the Appeals Court. However, more than a legal analysis, this case raises fundamental questions about the nature of the Guatemalan state, especially regarding the separation of powers and the exploitation of the justice system for political and economic ends. As one of the BDH lawyers aptly puts it:

“Criminal law seeks justice, but also social peace. Social peace cannot be achieved if community leaders, traditional authorities, or community representatives who lead territorial defense processes face majorly flawed legal proceedings.”14

Rigoberto Juárez and Ermitaño López’s criminalization has had a profound impact not only on their lives, but also on the social fabric of their communities and on the ability of the indigenous peoples of Guatemala to exercise their fundamental rights. The protracted nature of these processes causes exhaustion, fear, and fragmentation in spaces for community participation, weakening communities’ ability to exercise their right to self-determination. This case therefore challenges both Guatemalan society and the international community, since defending territory, water, and life cannot continue to be treated as a crime. Ancestral and community authorities, far from representing a threat to social order, are pillars of community cohesion and transmitters of ancestral knowledge. Criminalizing them not only violates individual rights but also undermines the collective rights of indigenous peoples as recognized by national and international law.

UPDATE February 10, 2026

The Constitutional Court (CC) confirmed the sentences against indigenous authorities Rigoberto Juárez Mateo and Bernardo Ermitaño López Reyes and maintains a sentence of 8 and 24 years in prison respectively.

1 United Nations General Assembly, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples, James Anaya. Extractive industries and indigenous peoples, 11 Sep 2013.

2 Grupo Internacional de Trabajo sobre Asuntos Indígenas (IWGIA), Guatemala: Corte sentencia que Convenio 169 tiene jerarquía constitucional, 24 Mar 2010.

3 United Nations General Assembly, Op. Cit.

4 In 2023, the Maya, Xinka, and Garifuna population of Guatemala represented 38.8%, according to the National Institute of Statistics in Guatemala, and 43.75% according to the International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs (IWGIA).

5 Iniciativa para la Reconstrucción y Recuperación de la memoria Histórica (IMH). El Camino de las Palabras de los Pueblos, Magnaterra Ediciones, Guatemala, 2013.

6 Rodríguez-Carmona, A. y De Luis Romero, E., Hidroeléctricas insaciables en Guatemala. Una investigación del impacto de Hidro Santa Cruz y Renace en los derechos humanos de pueblos indígenas, 24 Jun 2016.

7 Villatoro, D., La espera de los líderes comunitarios en prisión: ¿criminalización o justicia?, Plaza Pública, 11 Apr 2016.

8 Bastos, S., El juicio a las autoridades comunitarias del norte de Huehuetenango: defensa del territorio y criminalización, Revista Eutopía 4(2), 01 Dec 2017.

9 Tzul, G., Peritaje socio cultural. El rol de las autoridades indígenas en la mediación y resolución de conflictos, Revista Eutopía 4(2), 01 Dec 2017.

10 Cadena, R., Peritaje sobre el fenómeno de la criminalización de la protesta social a la luz del derecho internacional de los derechos humanos, Revista Eutopía 4(2), 01 Dec .2017.

13 Ibid.

14 Ibid.