“we fight to protect what our grandfathers and grandmothers achieved.”

[published in Bulletin 51, July 2024]

In October 2023 PBI began accompanying the Indigenous Community of San Francisco Quezaltepeque, in response to the numerous threats received by those who lead the defense of the rights of the Maya Ch’orti’ people.

The municipality of San Francisco Quezaltepeque lies some 200 kilometers east of Guatemala City, on the slopes of the volcano of the same name. Archaeological studies identify Quezaltepeque – which means hill of the quetzal birds in the original Nahuatl language – as one of the territories historically inhabited by the Maya Ch’orti’ People. Before the Spanish invasion the cultural and political center of this territory was located around Copán, which is now part of Honduras.

The Ch’orti’ territory in Guatemala extends across the municipalities of Olopa, Camotán, Jocotán and San Juan Ermita in the department of Chiquimula, and the municipality of La Union, in the department of Zacapa, where a total of more than 100,000 Ch’orti’ Mayas live.

Historical memory of the Ch’orti’ People of Quezaltepeque and their land rights

The principal demands of the Ch’orti’ People of Quezaltepeque, who have managed to reconstruct their history from the Spanish invasion from 1525 and 1530, are the recognition of their ancestral identity and the recovery of their territory and their rights as an indigenous people.

According to the Poqomchi’ anthropologist and political analyst Máximo Ba Tiul, the arrival of the Spaniards marked the beginning of the process of dispossession and plunder against the native peoples, promoted by the Spanish Crown and the Catholic Church. In the case of the Ch’orti’ people, the invasion of Quezaltepeque by Pedro de Alvarado resulted in the confiscation of lands and the reorganization of the population as a labor force under the orders of the Spaniards. The Catholic Church played a fundamental role in the conquest, by using religious brotherhoods to pursue the submission of the indigenous population to the social and religious structure of the colony. The reconstruction of the history of the brotherhood of San Francisco Quezaltepeque, which is still preserved by the Indigenous communities today, has allowed the Ch’orti’ People begin to raise awareness of the history of the dispossession of their lands.

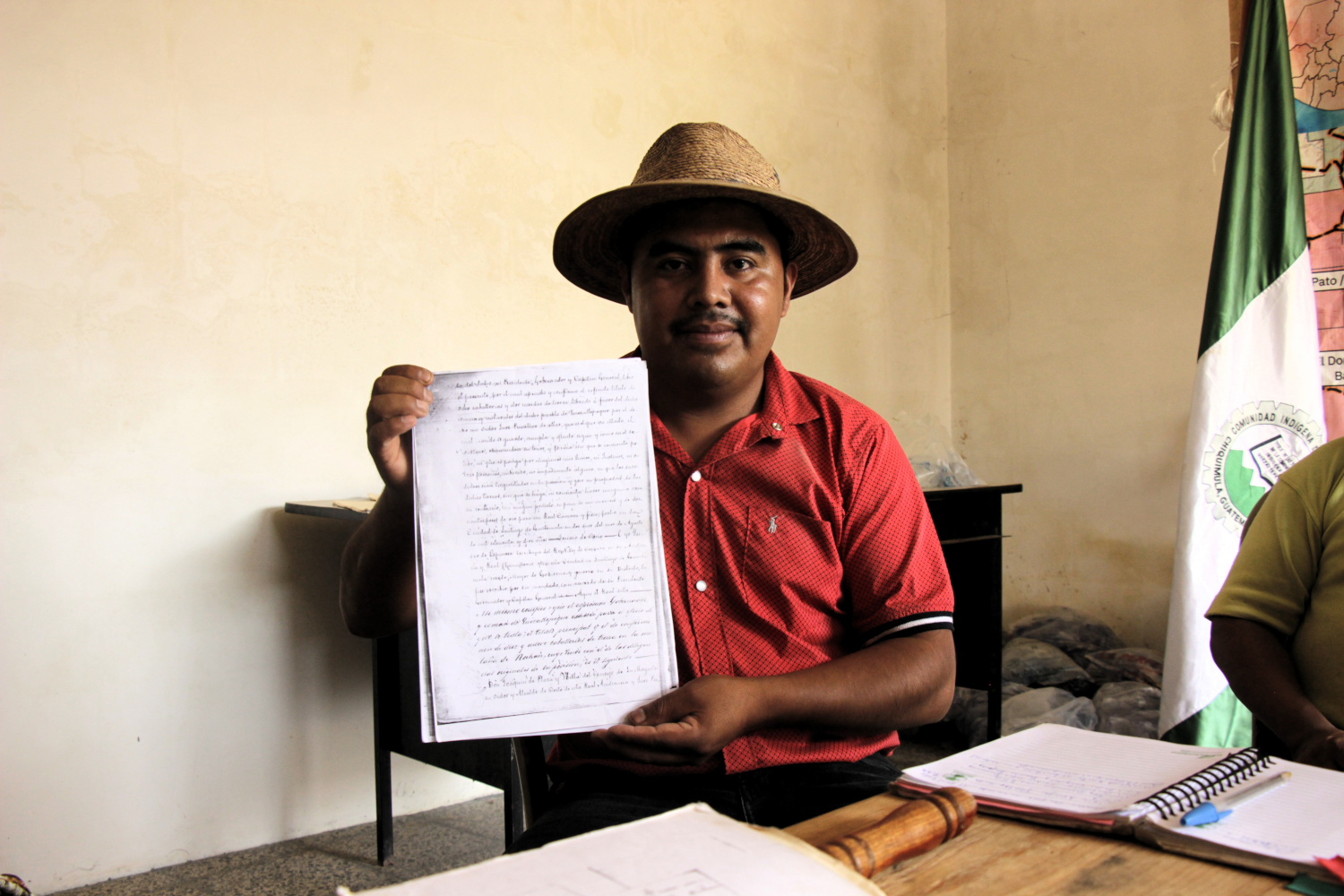

Using documents recovered from the period between 1710 and 1805, the Ch’orti’ of Quezaltepeque have confirmed that their ancestors bought approximately 243 caballerías of land from the Spanish Crown which had been violently taken from them, in the estates of La Cofradía, Nochan, Ejidos and Corral Falso. Approximately 60 years later, on August 14, 1866, the new State of Guatemala (founded in 1821) delivered the certification of the unified ownership of these lands in the name of the common Indians of San Francisco Quezaltepeque, which remains in the hands of the communities to this day.*

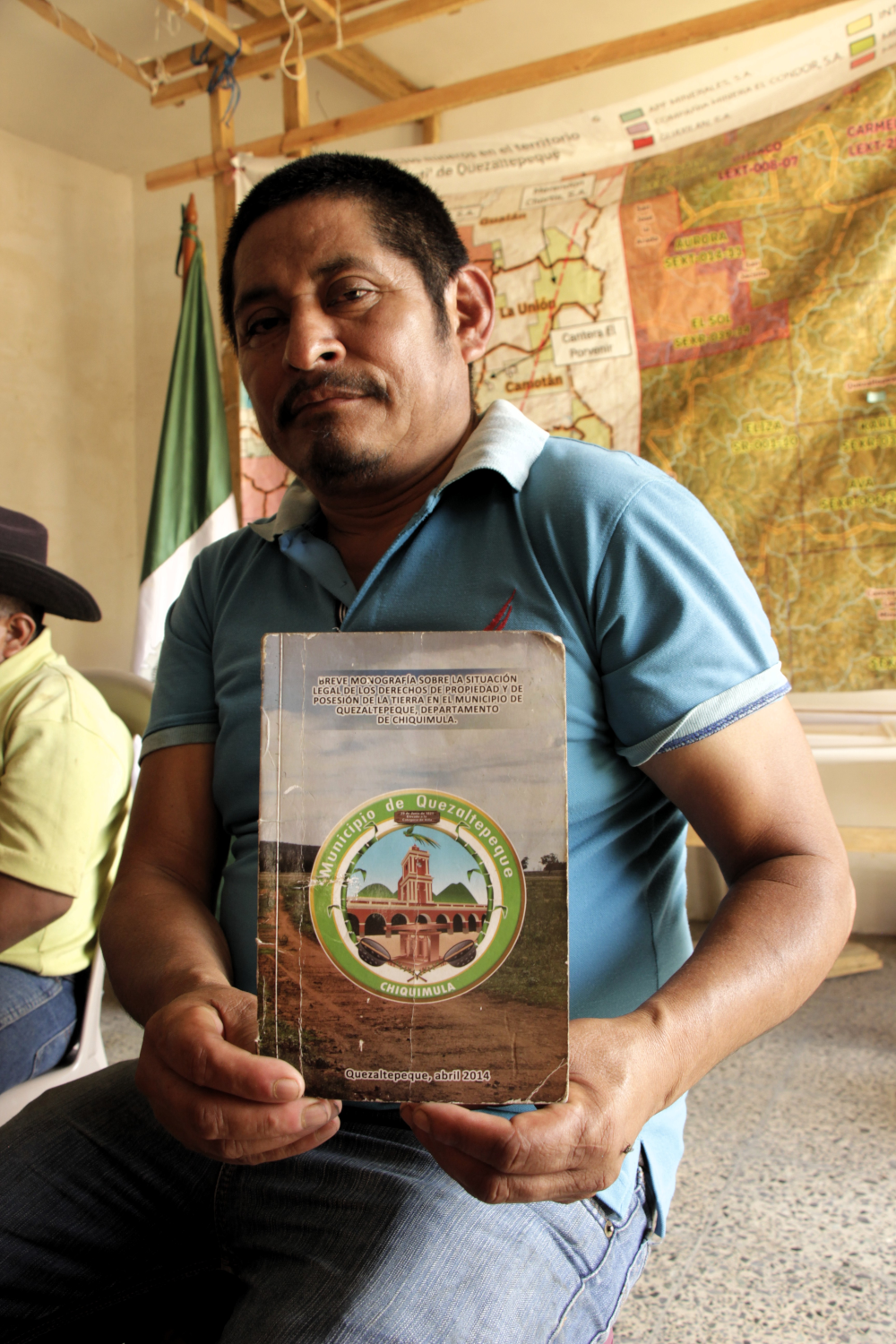

However, the newly created State of Guatemala remained a tool of the Criollo class who continued with the dispossession of indigenous lands and territories. Many of the laws passed by various governments during the liberal reform were used for this purpose. For example, during the government of Justo Rufino Barrios the expropriation of indigenous communal lands was facilitated through the approval of several decrees. The lands were first registered in the name of the newly created municipalities and then sold at public auctions.6 In this regard, Marvin Arnoldo Nájera López, indigenous authority of San Francisco Quezaltepeque, highlights how in his research he discovered that the historical title of the lands purchased by their grandfathers and grandmothers appears in the land registry, but that the same lands are also registered in the name of the State or, in this case, the municipality.

The State of Guatemala legally recognized the Ch’orti’ people of Quezaltepeque in 1958, granting them legal status as an association, under the name of the Indigenous Community of San Francisco Quezaltepeque. This poses a further problem, according to Nájera López, because “the historical title to the lands is in the name of the common of natural Indians of San Francisco Quezaltepeque, which does not coincide with the name under which the State registered the organization of the Ch’orti’ People. The State wants to use this discrepancy in the names to take away our land rights. They wanted to reduce us to an indigenous community, but a community is nothing if it is not attached to a people.” In order to vindicate their existence as Indigenous Peoples, the Ch’orti’ of Quezaltepeque have recovered the figure of Indigenous authorities as of 2021. “The name with which we constituted ourselves, Maya Ch’orti’ Indigenous Authorities of San Francisco Quezaltepeque, refers to the fact that we are the Indigenous authorities, that we belong to the Maya Ch’orti’ People and that we are from San Francisco Quezaltepeque, just as our lands are titled.” The 23 Ch’orti’ communities and 96 hamlets comprising the territory annually elect eight members of the board of directors of the Indigenous Community. Once their term of office is over, the members of the board of directors can become part of the Indigenous authority, a position they hold for life. The appointments of the new authorities, which is symbolized in the act of granting a ceremonial rod, are carried out in a public ceremony, sworn in by authorities from other people, such as the Ch’orti’ of Olopa, the Xinka of Jalapa or the K’iche’ of Totonicapán, demonstrating the alliances that exist between the different peoples.

In the face of the State’s strategy of ignoring the existence of indigenous peoples, the Ch’orti’ population of Quezaltepeque has also kept their ancestral traditions alive as these continue to connect them with the territory they inhabit. An example of this is the ceremony that takes place every April 23, the beginning of the rainy season, at the source of the La Conquista River. Since pre-colonial times, this ceremony celebrates the importance of water and the rains, and today it allows the defense of the natural assets of the territory, giving it a sacred value.

Threats and challenges facing the indigenous community of San Francisco Quezaltepeque

The Ch’orti’ of Quezaltepeque currently face several threats to their existence as a people. The principal threat arises from the racist and colonial history described above, which means they continue to be confronted with a State that ignores their existence and thus violates their collective rights, recognized through international instruments such as Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization (ILO) or the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. This is evidenced by the permissiveness of the municipality of Quezaltepeque with respect to the privatization of communal lands. The breaking up of land, lack of recognition of sacred sites and concessions to undertake private activities, all affect the heritage of the Ch’orti’ People. One example is the granting of a permit to drill a water well in the community of San José Cubilete at the site of a sacred cemetery for the Ch’orti’ People without prior consultation with the communities. Regarding this case, the Court of First Instance for Criminal and Narcoactivity of the Department of Chiquimula ruled in December 2023 that the municipality of Quezaltepeque did not conduct a prior dialogue with the communities involved and suspended the drilling of the well, out of respect for the right to consent of the Ch’orti’ People.

Another example is the municipality’s attempts8 at declaring the territory of the Quezaltepeque volcano to a protected area within the Trifinio Plan, without the free, prior, and informed consent of the Ch’orti’ People, who have ancestral ownership of the territory, and without clarifying what participation the Ch’orti’ communities would have in the management of the protected area. Regarding the management of the volcano, the indigenous authorities are also concerned about the municipality’s desire to promote tourism activities in this territory which is sacred to the Ch’orti’ People, again without prior consultation with the communities. According to Marvin Nájera, “the municipality wants to develop a training plan for tourist guides, so that they can show them the riches of the volcano’s lands. This is a new threat, not only that private interests will take advantage of our communal resources, but also that more foreign interests will come to these lands with the aim of exploiting these resources.”

The exploitation of resources without their consent is another concern of the Ch’orti’ People who, in 2022, discovered the existence of five applications for mining exploration licenses filed in 2010 by Minerales Sierra Pacífico S.A., a subsidiary of the Canadian company Radius Gold Inc. for the exploration of gold, silver, copper, lead and zinc: “they are still in the application phase, but we are afraid that at any moment exploration could begin, again without us having been consulted.”

The volcano is a fragile ecosystem, made up of virgin forest that the Ch’orti’ People have been taking care of for centuries. Privatization of this territory is another problem the communities have denounced, along with the danger of excessive exploitation of forestry resources and the risk of fires. This is an increasingly vulnerable territory within the current context of climate crisis. To stop this threat, the indigenous authorities filed a complaint with the departmental delegation of the Human Rights Ombudsman’s Office (PDH) of Chiquimula in March 2024, against private individuals whom they accuse of seeking to appropriate a part of the communal lands of the volcano, located in the village of Chiramay, with the aim of selling them. The complaint led to an visual inspection of the site by the Public Prosecutor’s Office (MP) a month later. The objective of the inspection was to gather evidence of the denunciation which led to the initiation of legal proceedings in the Specialized Prosecutor’s Office against the Crime of Invasion.

The defense of water also leads to confrontations between the Ch’orti’ People with economic interests that have been making private use of communal resources. Coffee production in the area and, specifically, the discharge of polluting wastewater from the coffee cleaning process into the River Grande and artificial wells is affecting the lives of more than 10 communities and their water sources. The inhabitants, some 150 families, report foul odors, dead fish and skin diseases. For the past five years, these communities have been unable to use the water sources for fishing, washing or drinking water. In order to defend their right to water, the communities filed a complaint against Ovidio Cardona and his company “Café La Conquista” in 2022. The investigations are being carried out by the environmental prosecutor’s office of Zacapa, but to date there has been no judicial resolution to the problem.

The Indigenous authorities of Quetzaltepeque have been subject to verbal threats, attacks on their property, criminalization processes and even physical aggression as a result of their work in denouncing these violations and in defense of their rights.

This prompted their request for international accompaniment from PBI. “The authorities are being singled out and we risk our lives defending our collective rights,” said Rolando Castillo Romero, an indigenous authority from the Nochan farm. “With the accompaniment https://www.facebook.com/muniquezaltepequewe feel encouraged to continue in this important struggle.”

* This information, and all other information not otherwise footnoted, was provided by the Indigenous Community of San Francisco Quezaltepeque in an interview that PBI held with several of its leaders on April 17, 2024.