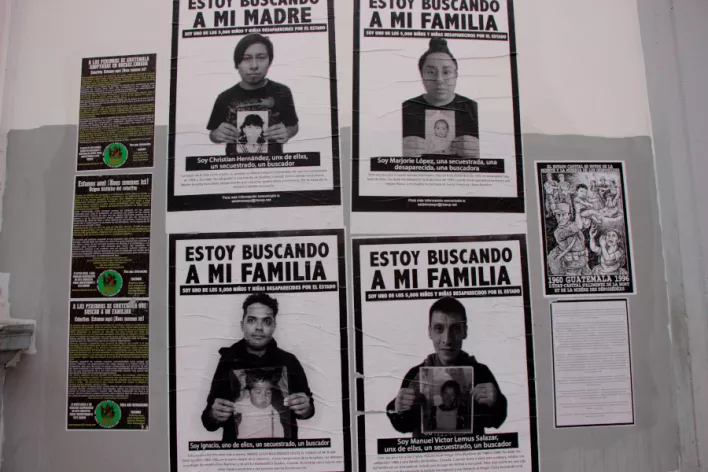

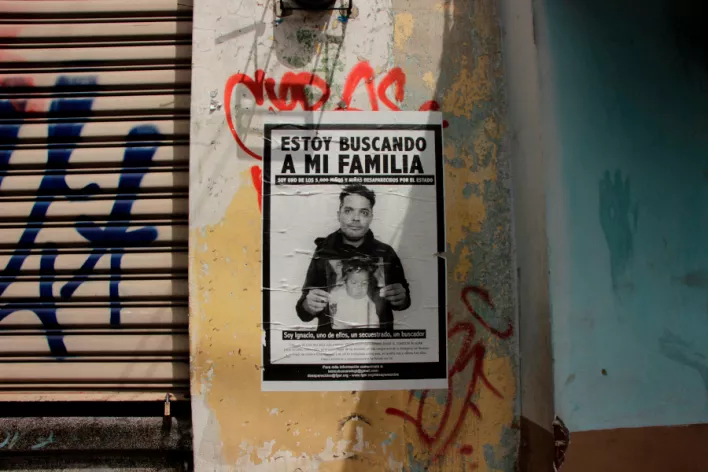

For some years now, walking through the streets of the historic center of Guatemala City, we are astonished by the hundreds of photographs that paper some of its walls. They are the faces of people who disappeared during Guatemala’s Internal Armed Conflict (IAC), lasting over three decades, and ending with the signing of the Peace Accords in December 1996. More recently, these have been accompanied by images of young people carrying photographs of themselves as children or babies and who are now looking for their families.

On February 25, at the march for the National Day for the Dignification of the Victims of the IAC, we met Ignacio, Juana-Iris and Marjorie, members of the Estamos Aquí - Nous sommes ici (We Are Here) collective, founded by people born in Guatemala and adopted to Quebec (Canada). A week later we interviewed them and they told us part of their stories.

How did this collective begin?

Ignacio: Three years ago a friend sent me an article about child trafficking. I read it and it had a big impact on me, it was a “shock” for me. The following year, I decided to return to Guatemala to begin the process of searching for my family by going to the Guatemalan Forensic Anthropology Foundation (FAFG) and giving my DNA. When I arrived in Guatemala 2 years ago I had no contacts; I had not lived here in the capital, I had lived elsewhere, but not in the capital. I didn’t know what to do, where to go. I began to walk the streets of Sixth Avenue and there I became aware of the extent of the armed conflict through the photos on the walls. That’s how I got to know H.I.J.O.S1 Guatemala. When I saw those photos I realized how terrible the conflict had been and that families were looking for their disappeared. It was a very important moment for me, because my story is the other way around: I am “the disappeared looking for his family” and not “the family looking for their disappeared.” The following week I met the gang from H.I.J.O.S Guatemala and I shared my idea with them. They said they would support me and they did, they helped me a lot. We took photos for papering the streets and organised a press conference. From then on I started receiving emails from people who had also been adopted and who had doubts. That’s how it started.

Back in Canada, during the pandemic, I realized how difficult it is to begin searching with so few tools, no contacts in Guatemala, no political context and without speaking the language… you don’t know where to start. It’s something that nobody teaches you. Society believes that if you want to start the process, that it’s your responsibility, because people assume that you were lucky to have been adopted. So, when I started receiving emails, the idea of forming a collective or organization to support people affected by illegal adoptions and trafficking of minors began to grow. That’s how I met Juana. But in general nobody talks about it, it is still very unknown.

In April 2021 we formed the collective. Our goal is to create a solidarity network between Guatemala and Canada so that people don’t feel alone, because this story is the story of a people, not only the story of the children who were adopted, but also of the Guatemalan families who lost them. We want to form a network of solidarity and begin this struggle among all of us. In Canada there are about 15-20 of us who have come together to get to know each other and share our stories and our experiences, which are very similar, even in regards to racism.

And how did you get involved in the association in Canada?

Juana: Talking to a friend who is also adopted from Guatemala and is looking for her family, the subject came up and she introduced me to Ignacio. In December 2020 I talked to him and he told me about his idea of creating a collective, because he thought it was important to help me and other people who have been looking for their families for a long time, so that we could find out the truth about our stories and if our papers were real. In Canada I wrote to the organization involved in my adoption and they told me that they do not work with Guatemala. But my papers include the name of this home and the name of this person. I wrote several times to this person and to the consulate, but got no response.

Faced with this lack of response, we talked to a journalist in Canada who was making a documentary about illegal adoptions to Canada. He invited me to participate and tell my story. There have been many children adopted to Canada. It is very difficult to live with this, there is no information, neither in Guatemala nor in Canada.

Marjorie: I met Ignacio the first time when I came to Guatemala in 2020. This trip changed my life because I did not expect to feel at home. After this trip I decided to start the process of searching my mom. I wrote to the Adoption Secretariat in Quebec. The waiting list was very long and I was told it would be a slow process. My adoption papers also contained information about my lawyer in Guatemala. I looked her up on Facebook and wrote her, she replied that it was a pleasure to meet me and that she was going to help me, but little by little she moved away from the case and no longer answered me.

I contacted the “Association of Guatemalans in Quebec” to ask if they helped to find relatives in Guatemala. They replied that they did not. But someone from their association told me about the Facebook page for the collective. I wrote to Ignacio and then we talked on the phone and he told me that the collective could help me, that I was not alone in this journey; and so, little by little I became aware of everything that happens here in Guatemala.

After that I realized that I didn’t just want to look for my mom, I also wanted to know the truth. It’s important to me, that’s why I got involved in the collective. I am 29 years old and I never knew this story before and I don’t think it’s fair. I think that it shouldn’t just be me, other adopted people and parents who lost their sons and daughters, need to know the truth.

And it’s hard for me to understand how the Canadian government never became alarmed or questioned why there were so many adoptions of children from Guatemala, they closed their eyes to the situation. I can’t understand it, and it’s important for me to know the truth.

Adoption papers are the first clue in the search, do adopted people have access to these papers?

Juana: It depends on each case. I have many papers in French, English and Spanish. In the Spanish papers some things are different from the French papers and the same happens with the English papers. In another case, the woman involved has only one set of adoption papers and she does not know if it contains the real names of her parents or the correct dates. She doesn’t know if the papers include the truth about the city where she was supposedly born, nor the information about the adoption home.

Marjorie: In the 80’s it was easier to put children up for adoption without papers. But in my case, for example, I have many official documents, this does not mean they are more accurate, just that the adoption procedure was more “orderly.”

Ignacio: It’s difficult to know because we don’t have much information. I have been told that things began with the massacre in 1978, when they started taking children, and continued with the massacres that followed in Petén, Quiché, Chimaltenango, Quetzaltenango, the Verapaces and others. They also stole the babies of the pregnant women they had kidnapped and imprisoned for their militancy. They waited for them to give birth, took the baby from them and then murdered them. There are many girls and boys from the Coast and from the Capital. I believe that in a few years we will know more. We know of some cases in which they have already found their relatives and they have told us what happened. The young people who were adopted 30 years ago are now starting to organize themselves. We don’t have a lot of data, we don’t know what happened, but I think in a few years there will be more information.

M: In my documents there is a page that explains why, supposedly, my mother gave me up for adoption. The papers pretend that it is she who explains that she gave me up for adoption because she did not have the resources to take care of me. It also states that I have other siblings. I don’t know if this is true, but after talking to other people I see that we have a similar story where the mom doesn’t have resources, the region of the country varies, but the stories are similar.

Juana: I can say that, depending on the years, the stories of the children can vary, like those from the Capital. There are even papers that say the parents were violent.

Do you have data on the number of children affected and their ages?

Ignacio: I think we will never know the number of people affected, but we know that there are approximately 5,000 missing children and at the same time there are more than 35,000 children who were illegally given up for adoption. Thousands and thousands of children were sold, and all this started during the IAC. In the beginning the aim was to wipe out the peasants and the children of the peasants. They wanted to prevent the formation of future guerrillas and also to eradicate the Mayan culture. Then they began to steal those children. Then they extended it everywhere, but there were also families that “gave” them to hospitals.

When they were taken from their families and homes, most of the children were between a few days and four years old. We also know of cases of children who were eight and ten years old.

What is your wish regarding the search for justice?

Marjorie: For me it is important. On the one hand it’s a personal issue, of each person affected. Each child who was adopted experienced the situation in a different way, so each of us must decide how to deal with the situation. But it’s also a collective issue.

Juana: I think it’s something personal, but for me it is very important to get involved and help other people. That is my first objective, to help, since I know what it is like to live with this, I want to help other people who are looking for answers.

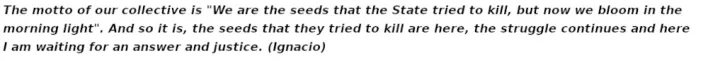

Ignacio: Well, I believe that this struggle is collective, autonomous, political and personal. That each person does what they want. For me the most important thing is to know what happened, what happened to our families, where the archives are. During that time they classified many files, in the People’s Registry they classified our surnames, dates of birth, the towns where we were born. It’s important for me to know the truth and to find justice in both countries. It feels more difficult here, it’s better back there. But yes, it’s the struggle of people like us; there are also people who are not searching and who don’t want to know anything, and we have to respect that. Each person has his or her story, and if someone wants to begin the search process, I am here. Also if you want to meet the people or know the stories, we will put you in touch. Everyone has their own rights and decides their own way of fighting.

What have you achieved as a collective in your first year of existence?

Ignacio: The collective is less than a year old, but we have been able to locate some families, we have done a report with Canadian television and we have met 15 or 20 other adopted people. I think we are doing quite well, but we have to give it time and keep in mind that this can be very emotional. At the moment we are creating a guide for adopted people around the world, which we will publish soon. We are gathering all the information for those people who want to come to Guatemala, so that they have this guide as a reference: where to go, where to ask for their papers, how and where to give their DNA, etc.

We are in contact with comrades in Montreal, France, Belgium, the United States…, we see that people are organizing themselves and that soon more people will arrive in Guatemala, as in the case of Marjorie, whom I accompanied. For me it is an interesting process, because accompanying them reminds me of the first time H.I.J.O.S. accompanied me. Now it was me who accompanied her. The collective is a space for people to come and not feel alone, because we are here.

1Hijos e Hijas por la Identidad y la Justicia contra el Olvido y el Silencio – Children for Identity and Justice against Forgetting and Silence.