“Sites of memory are there to say to society: yes, they lived; yes, they existed; and yes, the Guatemalan state committed these crimes against its own people even though it had a responsibility to protect their lives. For the families, it means reparation, dignity, receiving a minimum of justice, recognizing the truth that their loved one was indeed alive, that they were indeed murdered for defending human rights and seeking a dignified life: better wages, better education, land to farm and feed themselves, etc.”1

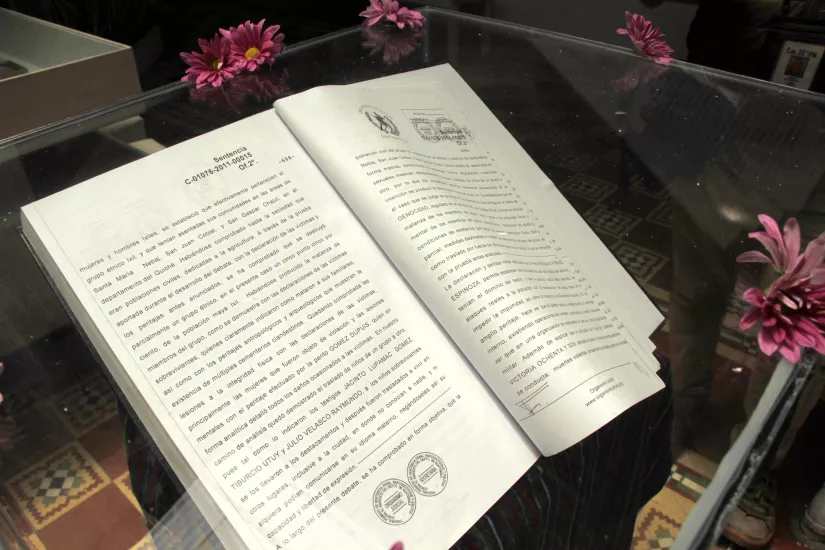

For the last decade, the struggle for justice in Guatemala has been marked by landmark trials that have contributed to the recognition of the country’s historical memory. Sentences in cases like the Dos Erres massacre, the Spanish Embassy massacre, the Ixil Genocide, Sepur Zarco and Molina Theissen recognize some of the atrocities committed by the Guatemalan state’s high-ranking military commanders against their own population during the Internal Armed Conflict (IAC). However, the State has been extremely weak in terms of its obligation to deliver justice, recognize the truth, offer reparations and thus guarantee the non-repetition of atrocities like those committed during the IAC.

The achievements on the road to justice are due to victims/survivors’ organizations, which have carried out an enormous amount of work to break new ground. Part of this work has been to design and create sites that share this history. This work has often been led by these same organizations through initiatives in their own communities.

Throughout 2024, a year marked by major setbacks in transitional justice, primarily caused by efforts to obstruct legal proceedings,2 we visited several sites of memory, which we will discuss throughout this article. For a society denied the right to memory and truth, these spaces are essential for raising awareness of the country’s recent and extremely bloody history, characterized by brutal state violence that destroyed lives, families, communities, cultural heritage and social fabrics. They are a way of educating new generations and thus contributing to the reconstruction of the country.

Schools at the museum“Sites of memory are there to say to society: yes, they lived; yes, they existed; and yes, the Guatemalan state committed these crimes against its own people even though it had a responsibility to protect their lives. For the families, it means reparation, dignity, receiving a minimum of justice, recognizing the truth that their loved one was indeed alive, that they were indeed murdered for defending human rights and seeking a dignified life: better wages, better education, land to farm and feed themselves, etc.”3

For the last decade, the struggle for justice in Guatemala has been marked by landmark trials that have contributed to the recognition of the country’s historical memory. Sentences in cases like the Dos Erres massacre, the Spanish Embassy massacre, the Ixil Genocide, Sepur Zarco and Molina Theissen recognize some of the atrocities committed by the Guatemalan state’s high-ranking military commanders against their own population during the Internal Armed Conflict (IAC). However, the State has been extremely weak in terms of its obligation to deliver justice, recognize the truth, offer reparations and thus guarantee the non-repetition of atrocities like those committed during the IAC.

The achievements on the road to justice are due to victims/survivors’ organizations, which have carried out an enormous amount of work to break new ground. Part of this work has been to design and create sites that share this history. This work has often been led by these same organizations through initiatives in their own communities.

Throughout 2024, a year marked by major setbacks in transitional justice, primarily caused by efforts to obstruct legal proceedings,4 we visited several sites of memory, which we will discuss throughout this article. For a society denied the right to memory and truth, these spaces are essential for raising awareness of the country’s recent and extremely bloody history, characterized by brutal state violence that destroyed lives, families, communities, cultural heritage and social fabrics. They are a way of educating new generations and thus contributing to the reconstruction of the country.

Schools at the museum

For Kaqchikel poet, writer and educator Luís de Lión, who was kidnapped and disappeared in 1984, children were “a blank sheet of paper on which to start writing a new story.”5 The poet’s vision coincides with museums’ approach to memory: one of their main objectives is to educate young people about the events of the IAC, using pedagogical methodologies to ensure that the issue is passed on to new generations. Andrea Plician, head of the House of Memory6 explains that, after the museum opened, teachers approached her looking for tools to address the issue in schools, as the formal education system does not provide for in-depth study of the IAC, despite the fact that several court rulings in recent years, including those in the Molina Theissen and Sepur Zarco cases, have demanded its inclusion. The House of Memory has responded to this need by offering courses for teachers which culminated in the development of a pedagogy of memory. It is thanks to the initiative of teachers themselves, taking their students to visit the museum, that something so transcendental is being brought into schools.

David Lajuj Cortez is the coordinator of the Rabinal Community Museum of Historical Memory, a town whose Achí people were severely affected by the violence. He explains that the museum is a regional model for addressing the topic of the IAC with students. They encourage schools and universities to visit their exhibition spaces. In addition to sharing the history of the IAC and recovering the memory of what happened, the museum addresses the impacts of violence on Achí culture, as well as the effects that the fear and silence inherited from the violence continue to have on Achí cultural and spiritual life.7

“There are many people who don’t know about this part of history. Often parents are unwilling to remember and talk about this history because it is very painful. So it is kept hidden and not shared with their sons and daughters.” David Lajuj Cortez

“In the footsteps of our ancestors”

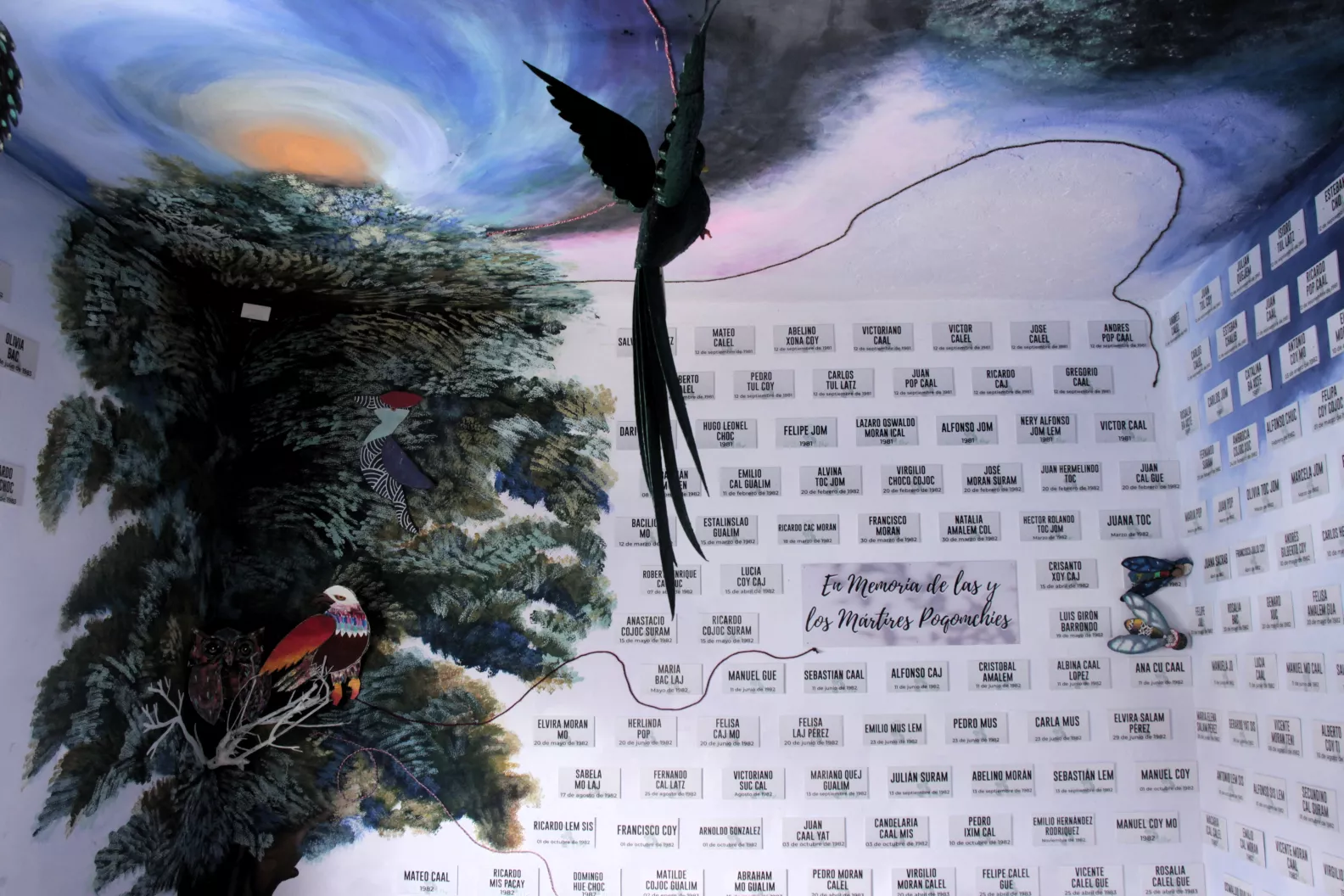

The Katinamit Museum of the Poqomchi’ Community Educational Center (CECEP) in San Cristóbal, Alta Verapaz, is a center for training, inspiration, reflection, advocacy, outreach and reinterpretation of the history and memories of the Maya people. The center trains young people to be community guides and peace promoters, and they pass on their knowledge to the students who visit the museum. They explain what the Poqomchi’ culture was like and how our ancestors counted time according to their indigenous cosmovision. The Hall of Martyrs honors and dignifies the memory of those murdered during the IAC and bears witness to their lives as leaders committed to solidarity and community work. The museum also pays special tribute to women elders who survived the violence, strong women whose lives and memories are shared through audiovisual media and a photographic exhibition featuring their faces. Henry Cal Jul, coordinator of the historical and ancestral memory process, explains that the museum, conceived of as an educational space, is constantly working to enrich its museography. Recently, the guardian animals of the nahuales have been incorporated in the Hall of the Martyrs. According to the Mayan worldview, they continue to accompany the spirits in the underworld. To recover ancestral memory, they have encouraged young people’s recognition of sacred and ceremonial sites in and around the municipality. These sites can always be visited by anyone who wants to learn about indigenous culture.8

Memory Tours

The María y Antonio Goboud (MAG) Foundation, located behind the National Library, in the center of Guatemala City, also promotes the training of memory guides as a collective process. The guides design tours and thus reclaim sites of memory in the historic center of the capital.

Sadi Car, memory guide at the MAG Foundation,9 explains that they have met young people who do not know their history; when they are told about the recent history of their country “it is as if they were hearing it for the first time.” Not even the students at the University of San Carlos de Guatemala (USAC), whose campus is marked by references to the student struggles of the 1970s and 1980s, know about the repression suffered by their predecessors. “We have met people who have never even visited Zone 1. For some it is difficult to understand what it means to reclaim public space and to understand why a space is contested, to understand the dispute over the truth, the struggle for justice, for finding the disappeared.” In the last two years, some 1,500 people have participated in the memory tours.

“The education system is one of the sectors that most refuses to acknowledge the truth, so one of our aspirations is for public establishments to get involved in our tours. We have seen more openness in private secondary schools, where students already come with some knowledge, but that is not the case in public schools.”

“The idea is for the right to memory to become normalized and recognized by everyone” Sadi Car

In the meetings that followed the tours, “we met visitors for whom it was a suffocating experience, as the past continues to be a taboo in society, but also in families. For example, it is common for there to be a disappeared family member but for the family not to talk about it.”

“Activism is not a crime”

Elisabeth Pedraza, coordinator of the human rights program of the Community Studies and Psychosocial Action Team (ECAP), has observed that family members live with the stigma that the disappeared or murdered person was “involved in something.” “In military discourse, activism was associated with crime. If you subverted the established order and did not accept the established norms, you were committing a crime, you were a criminal; and nobody wanted to be a criminal, because you were left alone. So, they disappeared your family member and you did nothing because you thought he had been a criminal and that the State had taken him away for being subversive. That has caused divisions in those same families. Nothing can be blamed on the State, it’s like the relationship between father and son, it’s a replica: the child has to subordinate himself to the highest authority, it’s a very vertical, patriarchal way of thinking, of total submission, very militarized. And we still have that in society, a fairly militarized structure; I have to be told what to do and that limits the possibility of cultivating your own abilities. It’s better to conform and you end up saying “let the authority figure tell me what to do”, that limits your capacity for thought and critical analysis; your critical thinking is overridden.

Marlon García, artist, archivist and museologist, questions the silence and the invisibilization of the lives of murdered and disappeared people: “It is worrying that museums sometimes overemphasize the idea of the victim, an eternal victimization. However, people were not only victims, so it is very important to ask what they did with their lives, how they responded to the army’s repression, what they did to survive and what victories they were proud of in the midst of so much violence.10

“They are not just numbers, they are not just names, they are people with qualities, histories, dreams and, of course, flaws too. The disappeared are human beings like us and that is why they must be made visible as such. If these wounds are not healed, it is impossible for Guatemala to build peace.” Mayarí de León

Gabriela Escobar, anthropologist and lecturer at the Rafael Landívar University (URL) specializing in processes of memory around the war in Guatemala, agrees with Marlon García. She insists that another step must be taken in the journey towards sites of memory, to move away from a focus on victims and suffering and to move towards celebrating struggles and victories, towards recognizing and vindicating activism, as the organization HIJOS has been doing since its founding in 1999. “The imposed stigmatization, silence and fear have prevented the disappeared from being recognized as the country’s heroes and heroines, since thousands of them were part of activism struggling to improve the living conditions of the Guatemalan people, who for centuries have lived in misery and without rights in a state ruled by economic interests.” “Nothing can justify the State’s disappearance and murder of these people, because in any case, if the people in question committed any crime, the State should have guaranteed them a fair trial. A state has no justification for taking the lives of its own people.”11 Both Marlon and Gabriela point out that international aid has also contributed to perpetuating the focus on the victims and they believe this should change.

The struggle for memory continues, it is not something that has already been won, as Sadi Car of the MAG Foundation points out: “When we finished the certificate program, we found out that the military veterans had started their own course on their memory at the Francisco Marroquín University. What we have learned is that there is not just ONE memory, but different memories; just as we defend our memories, they defend theirs. Memory is under constant dispute, as is public space.”

In the context of this dispute over memory, we cannot ignore the repeated attacks these places have suffered. Mayarí de León has reported that the plaque commemorating the disappearance of her father, the poet Luís de Lión, has been repeatedly destroyed with a hammer. The plaque is located at 2nd Avenue and 11th Street in Zone 1 of Guatemala City, the place where he was abducted. For her, each time the plaque is vandalized it is as if they had disappeared him again, “as if they would symbolically disappear him.”

The same thing happened recently with another commemorative plaque in the streets of downtown Guatemala City. The plaque read: “The parks, the university classrooms, the Guatemalan streets, are witnesses to the relentless struggles, the love, the solidarity and the smiles of thousands of university students. Because they gave their lives in search of a dignified Guatemala with social justice: Héctor Interiano, Carlos Cuevas, Gustavo Castañón and many, many more are PRESENT! ALIVE TODAY AND FOREVER! With the hearts of their families in the history and in the noble sentiments of the people of Guatemala. Forcibly disappeared between May 15 and 21, 1984.” Through a settlement with the State, this plaque was erected at the request of the family members of the disappeared young people, to commemorate their lives cut short by the Guatemalan State. In August of this year it was destroyed. The families replaced it on the Day of the Martyrs of San Carlos, held on the afternoon of October 30. The next morning it was destroyed again; there is no record of an investigation being opened.

These reprehensible acts – which, according to some of the people we interviewed for this article, have also occurred on the University of San Carlos campus over the last year – are encouraged by situations such as obstruction of trials and sentencing, or worse still, the total denial of justice, as in the case of the fourth trial for the Dos Erres massacre last year. This environment fosters impunity so that shadowy forces can vandalize sites that recognize the serious crimes committed by the state during the IAC.

According to Elisabeth Pedraza, the State should promote and protect the sites of memory and, consequently, accept its own responsibility as an apparatus of the State, since responsibility is inherited. There is a legacy that the State must assume, a historical responsibility towards its people. The State has the obligation to preserve these spaces and ensure that they are not destroyed but maintained, because they provide a sense of healing for families and Guatemalan society as a whole.

1 Interview with Elisabeth Pedraza, coordinator of the human rights program of the Community Studies and Psychosocial Action Team (ECAP), 05 Nov 2024.

2 See the article on the AJR in this Bulletin. In addition, the cases of CREOMPAZ, Diario Militar and Luz Leticia have faced a number of obstacles and setbacks.

3 Interview with Elisabeth Pedraza, coordinator of the human rights program of the Community Studies and Psychosocial Action Team (ECAP), 05 Nov 2024.

4 See the article on the AJR in this Bulletin. In addition, the cases of CREOMPAZ, Diario Militar and Luz Leticia have faced a number of obstacles and setbacks.

5 Quoted by his daughter Mayarí de León, in: PBI Guatemala: The Power of Words: Luis de Lión’s Legacy and the Diario Militar - Death Squad Dossier - Case, PBI Guatemala, Bulletin 46, December 2021.

6 Interview with Andrea Méndez, 12 Nov 2024.

7 Interview with María Hortensia Lajuj, Assistant Director of the Association for the Integral Development of the Victims of the Violence of the Verapaces, Maya Achí (ADIVIMA) and David Lajuj Cortez, 15 Oct 2024.

8 Interview with Henry Cal Jul, 17 Oct 2024.

9 Interview with Sadi Car, 27 Sep 2024.

10 Interview with Marlon García, curator of the Nuevo Horizonte Museum, Nuevo Horizonte, Santa Ana, Petén, 03 Dec 2024.

11 Interview with Gabriela Escobar, Guatemala, 30 Dec 2024.