Spaces dedicated to resolving the worrying escalation of the agrarian conflict,1 which is manifested in increased evictions of mostly indigenous communities, as well as cases of criminalization of land and territory defenders, are facing the highest level of closure since the signing of the Peace Accords.

This situation worsened considerably following the dissolution of the Secretary of Agrarian Affairs (SAA), whose functions were partially assumed by the recently created Presidential Commission for Peace and Human Rights (COPADEH). The Union of Peasant Organizations Las Verapaces (UVOC) and the Community Council of the Highlands (CCDA), both peasant organizations from the Verapaces who are accompanied PBI (the former since 2005 and the latter since 2018) are overwhelmed by the number of emergencies: evictions and threats of evictions; criminalization; imprisonment of community leaders; providing support to families; providing humanitarian aid to families who survived the recent storms but lost all their homes and possessions; 2 moral, economic and legal support to the families of murdered and disappeared members. All of this is in addition to their grassroots work in accompanying processes aimed at recovering land for dozens of indigenous and peasant communities.

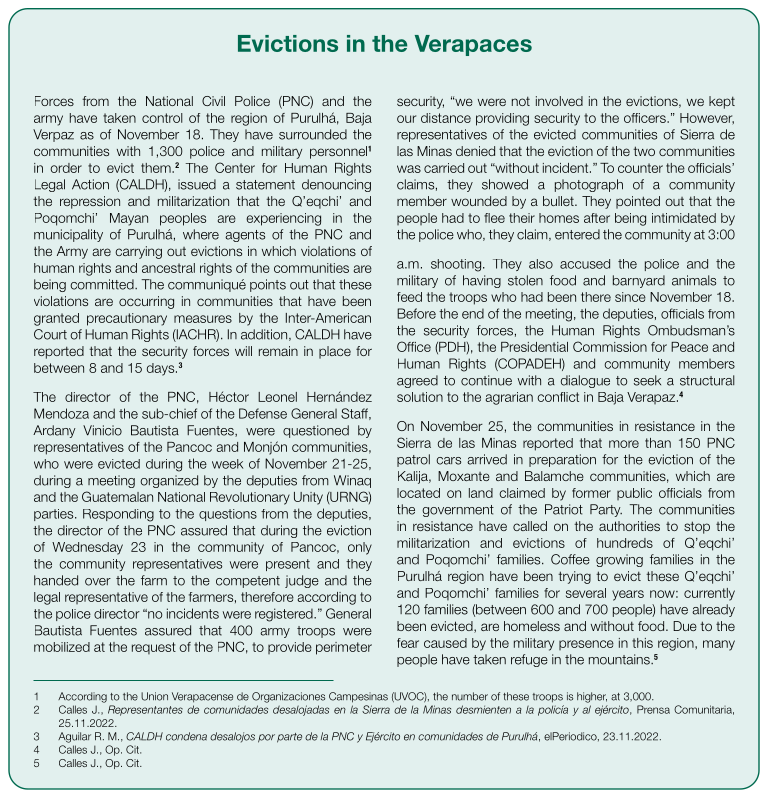

UVOC has registered 59 evictions since 2004 and currently estimates that 19 communities are at risk of eviction. In addition, they have registered some 1,000 cases of criminalization and provide legal representation to some 50 members of the organization in legal proceedings. Since 2011, 12 human rights defenders have been murdered and one person, Carlos Enrique Coy from Pancoc, Purulha, Baja Verapaz, has disappeared without, according to the organization, a serious investigation by the Public Prosecutor's Office (MP) into his disappearance.

Since 2018 CCDA has, unfortunately, lost seven members from murder and two who disappeared. In the case of one of the murdered members, two suspects were tried: one was released and the other was sentenced to five years of imprisonment which were designated as commutable. Lesbia Artola, coordinator of CCDA - Las Verapaces Region, has raised strong objections to this sentence: "we see that the life of a human rights defender is worth nothing." Only a few weeks before this resolution, in October 2019, two members of the CCDA, Jorge Coc and Marcelino Xol, were sentenced to 35 years in prison for homicide, in a process that, according to their lawyer, is plagued with irregularities.3

CCDA has a current register of 1,024 cases of criminalization corresponding to arrest warrants against members of the organization, including 324 women. In addition, they are supporting six imprisoned human rights defenders and their families. This year they have registered six extrajudicial evictions and three "supposedly" judicial evictions (according to CCDA, the eviction orders contain illegalities), which have left 125 families in absolute destitution: without housing, land or food.

The killings, criminalizations and evictions have caused a lot of suffering in families and communities.4 In recent years, violent judicial evictions and evictions carried out by non-state armed actors have increased. Indigenous communities are expelled from their ancestral territories and, in most cases, this occurs in departments that dedicate large tracts of land to mono-culture export crops. The high rates of poverty and extreme poverty in these regions are closely linked to the lack of access to land experienced by the majority of the population. Land is concentrated in the hands of a few who principally produce mono-cultures.

According to the latest National Survey of Living Conditions (Encovi) 2014, Alta Verapaz is the department with the highest poverty (83.1%) and extreme poverty (53.6%) in the country.

The emergence of the Association for the Defense of Private Property (ACDEPRO), created in 2019 by landowners in the Alta Verapaz region, has contributed considerably to the worsening of the conflict.5 Its purpose is to "promote, exercise and protect the right to property," from "international and national organizations that commit the crimes of trespassing and aggravated occupation and all related crimes against the private property of Guatemalans."6 ACDEPRO has been very present on different television and radio channels, and has issued press releases and held press conferences, denouncing the lack of action by the authorities in carrying out evictions on land that it claims is occupied by people from peasant NGOs. Organizations such as CCDA, UVOC and the United Peasant Committee (CUC) have faced defamation from this association, which accuses them of being "delinquents and trespassers" and belonging to "organized crime structures." ACDEPRO is using hate speech to delegitimize the work of the leaders of these organizations in defending access to land and the labor rights of the indigenous and peasant population.

The aforementioned peasant organizations strongly reject these accusations and vindicate their ancestral land rights in light of the dispossession they have experienced since colonial times - a right categorically rejected by ACDEPRO. The indigenous population have not only continued to lose territory, but they have also been forced to work for free for the landowners and the governments in power. It was not until 1945, during the government of Juan José Árevalo, that the congress abolished all types of forced labor.

The strong inequality of land tenure in Guatemala is a result of the history of dispossession and exploitation of indigenous peoples. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) "in Guatemala, 92% of small producers occupy 22% of the country's land, while 2% of commercial producers use 57% of the land" (2017).

Alliance between CACIF and the MP

Another concern for peasant organizations is the creation of the Property Rights Observatory by the Coordinating Committee of Agricultural, Commercial, Industrial and Financial Associations (CACIF). The objective of this Observatory is "to promote respect for the human right to property in Guatemala by monitoring, systematizing and communicating cases of violations of property rights, using official information sources that allow transparency and support the actions of public institutions in charge of guaranteeing these rights".

They signed a cooperation agreement with the MP at the launch. Six months later, on October 3, 2021, the MP declared it would "provide an effective and timely response to the Guatemalan population and ensure the protection of the human right to property, the Attorney General of the Republic and Head of the Public Prosecutor's Office, Dr. María Consuelo Porras Argueta inaugurated the Specialized Prosecutor's Office against the crimes of occupation, for the investigation and prosecution of the crimes of trespassing, aggravated occupation, alteration of boundaries and disturbance of possession." Between 2020 and 2021 the MP received more than 3.000 complaints related to the crime of trespassing/occupation.

The State has opted to address land conflicts through judicial channels, dismantling the state institutions responsible for finding peaceful and favorable solutions for all parties, created with the signing of the Peace Accords: the SAA, which was one of the commitments stipulated in the Accords, was disbanded in July 2020. Its functions were transferred to COPADEH, a recently created presidential agency, which only has a directorate for attention to conflict which, in two years of operation, has taken on all the country's conflicts, including those of a non-agrarian nature.7

From the SAA to COPADEH

According to Helmer Velásquez, UVOC's political advisor, the SAA was a leading institution, created for the prevention and resolution of agrarian conflicts in Guatemala. It had a trained team dedicated to political-strategic design and implementation, providing assistance and intervention on the fair and equitable resolution of land disputes. The SAA’s "quality was improving, it had bilingual staff - which was a demand from the peasant organizations - and had a very extensive background, very good archives on land conflicts and was very well documented." 8

Although the SAA had its flaws, Velásquez says the institution had the capacity to resolve agrarian conflicts. Jorge Luis Morales, member of UVOC’s legal team, agrees. He describes the SAA as an institution that had the institutional will to intervene in and manage specific demands for land titles, despite the political difficulties.9

UVOC’s coordinator, Carlos Morales, and Jorge Luis Morales, have highlighted how, during the existence of the SAA, there were slow – but significant – achievements obtained, with an important impact on the lives of hundreds of indigenous and peasant families.

According to the peasant organizations, the replacement of the SAA by COPADEH has meant a reversal of the slow institutional advances resulting from the Peace Accords. According to Carlos Morales, despite the willingness of its staff, the Commission's management capacity is limited by the lack of resources for monitoring and assistance. Velásquez also says that this is a small unit considering the magnitude of the agrarian issue in Guatemala: "the institution is inoperative, we may be able to count on it, but the rest of the public institutions do not pay attention to it, they cannot respond to its requirements. They say, very honestly, that they do not have the capacity, nor the personnel, nor the possibility of going to the countryside."

Peasant and indigenous organizations are now worried about what the future holds, because after years of demanding their rights, they have found that the processes for recovering land are at the mercy of the political will of the governments in power. However, they reaffirm their commitment to maintaining an open dialogue with the existing institutions, even if they falter and the challenges become ever greater. In the face of potential despair, they understand that their struggle for land and the defense of the territory has a long history. For this reason they will continue to organize and build networks, because, as Carlos Morales affirms, their struggle is for life itself, in dignity.

1 By agrarian conflict we mean the set of disputes over land interests and rights that have their roots in the historical structural conditions of land tenure and ownership configured in the country. The main economic activities that generate conflicts include agroforestry, hydrocarbon exploration and exploitation, mining, monocultures (palm oil and sugar cane), cattle ranching and energy generation and transportation.

2 The government approved States of Calamity in order to attend to the immediate needs of the affected families. However, one month after the storm Julia (October 2022), state institutions have not spent any of the Q540 million allocated in responding to the emergency and reconstruction work (in: Del Águila, J., Sin ejecutarse Q540 millones bajo estado de excepción, Prensa Libre, 8.11.2022). In addition, the accompanied organizations explain that state aid never reaches their communities. If it does arrive, it only goes to communities who are not claiming their land rights in recognition of their support for the economic projects installed in their regions.

4 PBI Guatemala: Bulletin 39, August 2018 y Now there is nowhere to plant. Life after eviction, Bulletin 38, August 2017.

5 For further information see: Solano, L., La estrategia de despojo del territorio y los apologistas de la propiedad privada, El Observador. Análisis Alternativo sobre Política y Economía No. 78.

6 Many of the association’s pronouncements are available on their Facebook page (@acdeproGT).

7 In 2022, according to its work report of the second trimester 2022, COPADEH dealt with 83 national cases, 58 of which were agrarian in nature. It has only eight roundtables for dialogue to deal with these conflicts.

8 Interview with Helmer Velásquez, October 2022.

9 Interview with Jorge Luis Morales, October 2022.